There’s an obvious risk to reopening the economy during the pandemic, even in places where the number of COVID-19 cases is dropping: As more people come back into contact, cases could surge again, and businesses could be forced to shut down a second time. South Korea is seeing a new spike in cases after the outbreak seemed to be under control. In China, new cases have emerged in Wuhan, the original epicenter of the virus. But an adjustment to work schedules—along with social distancing and other tools like contact tracing—could help businesses that can’t work remotely to potentially reopen safely.

The idea hinges on simple math. After someone is infected, it takes an average of three days before they can infect someone else. That means that people can theoretically work or attend school together for a short time if they then spend another stretch of time on lockdown—four days of work followed by 10 days at home. If they have gotten sick during their time at work, it will show up during their 10 days off and they won’t come into work for their next 4-day shift.

“The idea is that people will work in two-week cycles,” says Ron Milo, a professor of computational and systems biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, who worked with other researchers to model the impact of changing work schedules. “They will be on the job for four days, and by the time they might become infectious, they will be at home in lockdown for 10 days. This will significantly decrease the number of cases resulting from each infection and thus gives a feasible strategy for a return to economic activity that can prevent a second wave of COVID-19.”

When they modeled the alternating cycle of 4 days of work and then 10 days—the rest of that week, and the entire following week—off, the researchers found that the virus’s reproduction number, or the number of people that each infected person infects, dropped below one, meaning that the virus can die out. Some estimates suggest that without controls, the virus has a reproduction number between 4.7 and 6.6, making it far more contagious than the seasonal flu.

Variations on the schedule may also work. In Austria, schools will begin sending students to school in two different groups, each attending class in person for five days every two weeks. “The approach is flexible and adaptive and in our scientific paper, we analyze a wide range of possibilities that all function in a similar manner,” Milo says. “One can start with more days if there are strong indications that the spread is under control and on the decline. Four days of work is a conservative starting point, and if one observes a continued decrease in cases, more workdays can be allowed.”

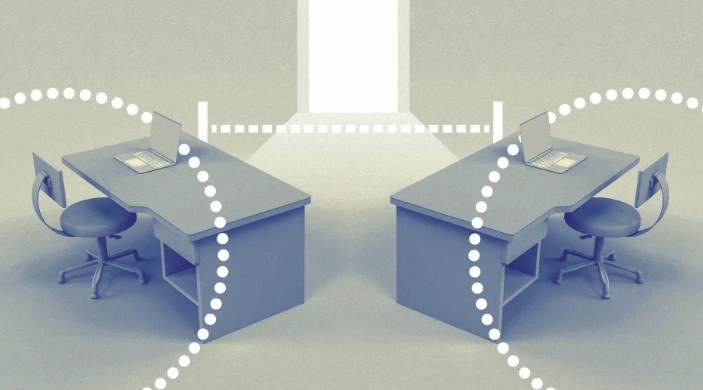

For businesses that need people present to run, the schedule could allow for continuous operation if people can work in alternating groups. For employees, it could allow for part-time work while protecting workers’ health; having fewer people in an office or factory at a given time will also help reduce the risk of infection. But at companies where employees can all work remotely, Milo says, they should continue doing so. This “is a shared societal effort to suppress COVID-19. Those who can be almost as effective, or more effective, by working remotely should continue to do that, and thus help decrease the overall spread. In a way, they are helping those that do not have that freedom and must go to work out of the house.”

The approach isn’t a panacea—retail stores and other businesses that interact with the public will still need to take extra precautions to slow the spread of the virus, such as curbside pickup for orders and wearing masks. The strategy “should be added to measures including physical distancing, hygiene, and protection of at-risk populations,” Milo says. “Business should take those measures while opening up.” But it could be done even without the type of widespread testing that many public health experts say is necessary for safe reopening before there’s a vaccine or effective treatments for COVID-19. It also means that in some areas, businesses could potentially open safely earlier than they otherwise would have been able to and employees could start being rehired to work, at least on a part-time basis. That could help build more public support, as Milo and researchers Uri Alon and Eran Yashiv wrote recently in The New York Times:

“It prevents the economic and psychological costs of opening the economy and then having to reinstate complete lockdown when cases inevitably resurge. Giving hope and then taking it away can cause despair and resistance.”

“The danger of a second wave, a resurgence of the epidemic, that will necessitate going back to full lockdown is higher under full reopening of the economy, especially if the number of cases has not been steadily declining and the infrastructure for contact tracing is not well established,” says Milo. “Our suggestion gives a predictable schedule that people can adapt to and builds confidence for people and the economy.”