REHOVOT, ISRAEL — January 7, 2026 — In the future, quantum computers are anticipated to solve problems once thought unsolvable, from predicting the course of chemical reactions to producing highly reliable weather forecasts. For now, however, they remain extremely sensitive to environmental disturbances and prone to information loss. A new study from the lab of Dr. Yuval Ronen at the Weizmann Institute of Science, published today in Nature, presents fresh evidence for the existence of non-Abelian anyons – exotic particles considered prime candidates for building a fault-tolerant quantum computer. This evidence was produced within bilayer graphene, an ultrathin carbon crystal with unusual electronic behavior.

In quantum mechanics, particles also behave like waves, and their properties are described by a wave function, which can represent the state of a single particle or a system of particles. Physicists classify particles according to how the wave function of two identical particles changes when they exchange places. Until the 1980s, only two types of particles were known: bosons (such as photons), whose wave function remains unchanged when they exchange places, and fermions (such as electrons), whose wave function becomes inverted.

“Our study brings scientists one step closer to developing fault-tolerant quantum computers.” —Dr. Yuval Ronen

In 1982, however, scientists discovered a new state of matter that enabled the existence of a third kind of particle, one that does not occur naturally. When these particles exchange positions, their wave function can rotate through any angle between 0 and 180 degrees – hence their name, “anyons,” from the word “any.”

Anyons appear only under extreme conditions – at temperatures close to absolute zero, in the presence of a strong magnetic field and strong inter-particle interactions, and only in two-dimensional systems: ultra-thin materials where vertical motion is impossible. Under these conditions, the electrons in the material stop behaving like whole particles and instead act like fractions of electrons – the anyons.

According to theory, there are two types of anyons. In Abelian anyons, exchanging places only adds a phase to the wave function; in non-Abelian anyons, the exchange not only adds a phase to the wave function but also alters its shape. Fractional electrons with an odd denominator (such as one-third of an electron) are Abelian anyons, whereas those with an even denominator (such as one-quarter of an electron) are believed to be non-Abelian.

“In non-Abelian anyons, the exchange of positions leaves an imprint on the shape of the wave function,” explains Ronen. “If we take three non-Abelian anyons and swap the first with the second and then the second with the third, we get a wave function that is very different in shape from the one we’d obtain if we exchanged them in another order. This provides a way to encode and store information – one of the key conditions for building a quantum computer.”

“In some existing models,” he adds, “qubits – the basic units of information in a quantum computer – are individual particles, which are sensitive to environmental noise. In non-Abelian anyons, information about the order of exchanges is stored not locally but in the wave function of the entire system. Systems whose essential properties are preserved at this level are resilient to local disturbances. Such systems are known as topological, and they offer one of the most promising routes to reliable quantum computation.”

Although scientists have recently succeeded in measuring Abelian anyons, non-Abelian anyons have not yet been directly observed.

From classical optics to quantum computing

In the new study, led by Dr. Jehyun Kim and Himanshu Dev of Ronen’s group in Weizmann’s Condensed Matter Physics Department, the researchers used the bilayer graphene – a sandwich of sorts, made up of two atom-thin layers of carbon arranged in a honeycomb lattice. In this recently developed material, the conditions expected to host non-Abelian anyons are stable, and the scientists can precisely control the anyons’ motion paths.

The Weizmann experiment drew on a famous 19th-century optics setup in which a light beam is trapped between two mirrors. Each time the beam hits and reflects off one of the mirrors, its wave function rotates by a certain angle, or phase. As long as the reflected beam is not synchronized with the original one, they cancel each other out, producing weak light. After several reflections, the wave function completes a full rotation and returns to its original phase, so the beams become synchronized, producing bright light. This creates an interference pattern of alternating light and dark bands, from which physicists can infer the properties of the original light wave trapped between the two mirrors.

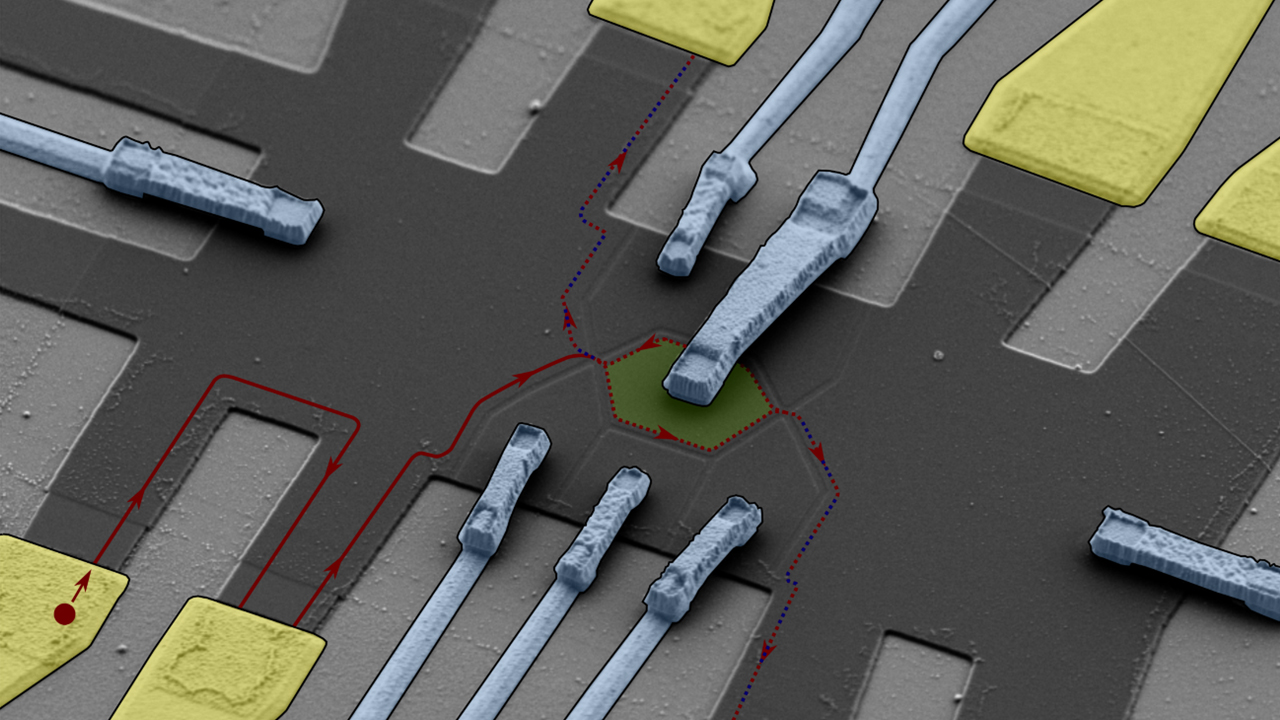

In the quantum version of this experiment, the researchers first tuned the electrons in bilayer graphene to a state expected to host non-Abelian anyons. They then created a looped path in which the wave of one anyon encircled an island containing other anyons and a magnetic field, before returning to meet its original wave.

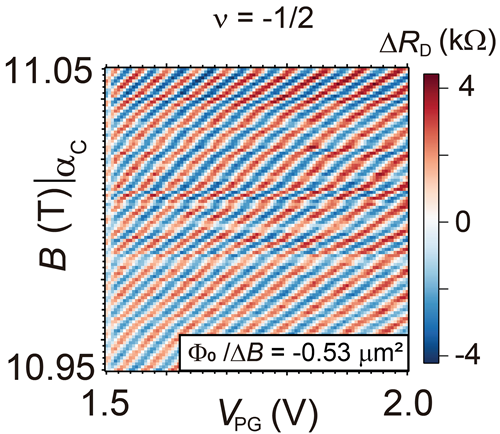

In the first stage, the researchers examined only how the magnetic field affected the phase of the orbiting anyon. With each revolution, the returning wave’s phase changed under the influence of the magnetic field, and when it met the original wave, they either cancelled or reinforced each other. As in the optical experiment, this produced an interference pattern, but here the pattern consisted of alternating bands of high and low electrical resistance, from which the properties of the encircling anyon could be deduced.

“In our experiment, we managed to measure a fractional electron with an even denominator,” says Ronen. “Contrary to the prevailing assumption that non-Abelian anyons carry a quarter of an electron’s charge, we were surprised to find that a wave corresponding to half of an electron was orbiting the island. Following additional experiments, we estimate that this occurs because two non-Abelian anyons are circling the island together, although we have not yet succeeded in separating them. Still, this represents an important step toward the direct identification and measurement of non-Abelian anyons, and we are now working on isolating them.”

The researchers then carried out another experiment to characterize the particles inside the island, which interact with the orbiting particle. By varying the electron density within the island and examining how this affected the wave function of the orbiting anyon, and therefore the interference pattern, they could deduce the properties of the island’s particles. Changes in the slope of the interference lines indicated that the internal particles carried a charge of one-quarter of an electron, as expected for non-Abelian anyons. This was consistent with earlier tunneling experiments in Prof. Moty Heiblum’s laboratory, also at the Weizmann Institute.

“We’ve shown that bilayer graphene almost certainly hosts particles that are non-Abelian anyons,” concludes Ronen. “The next step is to directly observe the ‘memory’ of a non-Abelian anyon system, in other words, to measure how each order of particle exchanges leaves a unique signature in the wave function. Today’s quantum computers are still limited to narrow research applications, and to become truly useful, they must be reliable. Our study brings scientists one step closer to developing fault-tolerant quantum computers.”

Also participating in the study were Amit Shaer, Dr. Ravi Kumar, Dr. Alexey Ilin, Dr. André Haug, Shelly Iskoz, Prof. David F. Mross, and Prof. Ady Stern from Weizmann’s Condensed Matter Physics Department; and Profs. Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi from the National Institute for Materials Science, Tsukuba, Japan.

Dr. Yuval Ronen’s research is supported by the Shimon and Golde Picker - Weizmann Annual Grant and the Schwartz Reisman Collaborative Science Program.