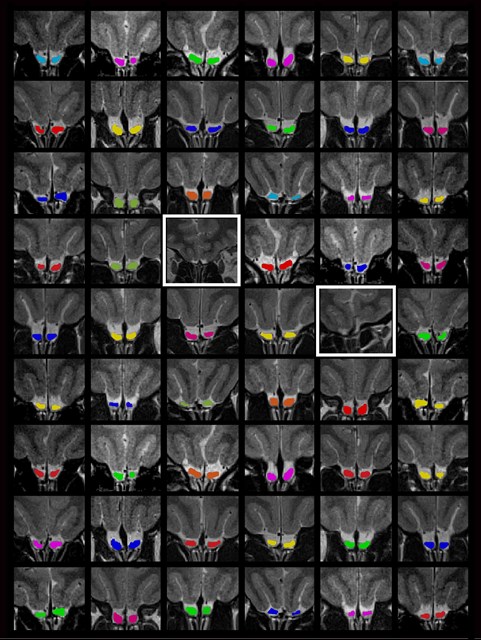

Computer-enhanced MRI images of the brains of left-handed women identified two that were missing olfactory bulbs

REHOVOT, ISRAEL—November 6, 2019—Is a pair of brain structures called the olfactory bulbs, which are said to encode our sense of smell, necessary? That is, are they essential to the existence of this sense? Weizmann Institute of Science researchers recently showed that some humans can smell just fine, thank you, without said bulbs. Their finding – that around 0.6% of women, and more specifically, up to 4% of left-handed women, have completely intact senses of smell despite having no olfactory bulbs in their brains – calls into question the accepted notion that this structure is absolutely necessary for the act of smelling. The findings of this research, which were published in Neuron, could shake up certain conventional theories that describe the workings of our sense of smell.

In the majority of people who have functioning olfactory bulbs, nerve signals from receptors in the nose first go through the bulbs before being passed onwards toward the olfactory center in the cortex. The prevailing theory has the olfactory bulbs combining the information from our noses’ six million receptors, comprised of some 400 different types, and encoding a unique “odor” signal to be passed on. Thus, unsurprisingly, some people who are congenitally anosmic ‒ that is, they never had a sense of smell ‒ indeed have no olfactory bulbs.

Although the centrality of the olfactory bulbs in olfactory perception is the “textbook” view, in the 1980s and 1990s some researchers removed the olfactory bulbs from the brains of rodents and found their sense of smell to remain functional. These findings, however, were not well received in the scientific community.

The new findings were unexpected: Drs. Tali Weiss and Sagit Shushan of Prof. Noam Sobel’s lab in the Department of Neurobiology were at Weizmann’s Azrieli National Institute for Human Brain Imaging, conducting MRI scans of subjects’ brains. One of the subjects, who had stated that her sense of smell was normal, was found to be lacking olfactory bulbs in her brain. The subject insisted: her sense of smell was not only normal, it was excellent. “We tested her smelling faculties in every way we could think of, and she was right,” says Prof. Sobel. “Her sense of smell was indeed above average. And she really doesn’t have olfactory bulbs. We conducted another scan with especially high-resolution imaging, and saw no signs of this structure.”

At first the researchers, led by Dr. Weiss and research student Timna Soroka, thought this might be the sort of exception that does not disprove the rule. They took functional MRI (fMRI) scans of the subject’s brain and compared them with those of a control group. But they needed a unique control group: since the subject was female and left-handed – both traits that can influence the organization of the brain – the researchers invited other left-handed women to have their brains scanned for comparison. “When the ninth subject in the control group also turned out to be lacking olfactory bulbs, alarm bells started ringing,” says Dr. Weiss.

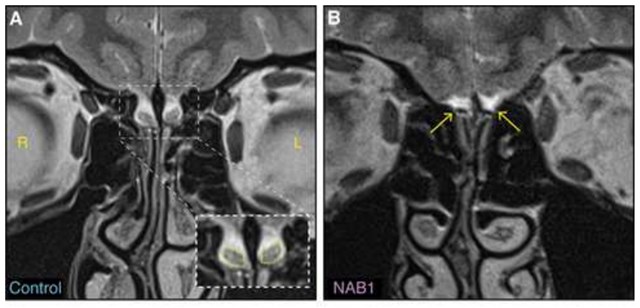

MRI of two brains. Both the woman on the left, who has intact olfactory bulbs, and the woman on the right, who is missing them, have excellent senses of smell

The olfactory bulb, at around 58 mm cubed in volume, is visible to the naked eye in images, but, says Prof. Sobel, if someone is not specifically looking for this structure, they are liable to miss it – or miss its absence. And because the differences connected to handedness can complicate datasets, some researchers even stick to right-handers, assuming that their findings on such things as the olfactory system will be relevant to left-handers as well.

However, once the Sobel team started looking for evidence for this phenomenon, they found it in an existing database: that of the Human Connectome Project. Out of the 1113 brain scans in this database, many of them of identical twins, some 10% are from left-handed individuals – which is around their incidence in the general population. Among the records contained in this open database are the results of smell tests given to the subjects. Dr. Weiss and Soroka, with the help of Liav Tagania, a high-school student working on an educational project in Sobel’s lab, searched through the information in the database. They did not find a single male who had both an intact sense of smell and a missing olfactory bulb, but they did find four women with both. And of those four women, two were left-handed. “Even more amazing was the fact that the two left-handed women were identical twins, and their twin sisters did have olfactory bulbs. Each of those with no olfactory bulb in their brains scored better on the smell test than their intact twin sisters,” says Soroka.

How do these “exceptions to the rule” square with the commonly held view of the sense of smell? There are several possible explanations. One is that the highly plastic brain creates a “smell map” in a different part of these women’s brains. But another possibility is that these exceptions do disprove the rule.

“Current ideas posit the olfactory bulb as a ‘processing center’ for information that is complex and multidimensional, but it may be that our sense of smell works on a simpler principle, with fewer dimensions. It will take high-resolution imaging – higher than that approved for use on humans today – to resolve that issue,” says Prof. Sobel. “But the fact remains that these women smell the world in the same way as the rest of us, and we don’t know how they achieve this.”

Prof. Noam Sobel’s research is supported by the Sara and Michael Sela Professorial Chair of Neurobiology; the Azrieli National Institute for Human Brain Imaging and Research, which he heads; the Norman and Helen Asher Center for Human Brain Imaging; the Nadia Jaglom Laboratory for Research in the Neurobiology of Olfaction; the Fondation Adelis; the Rob and Cheryl McEwen Fund for Brain Research; and the European Research Council.