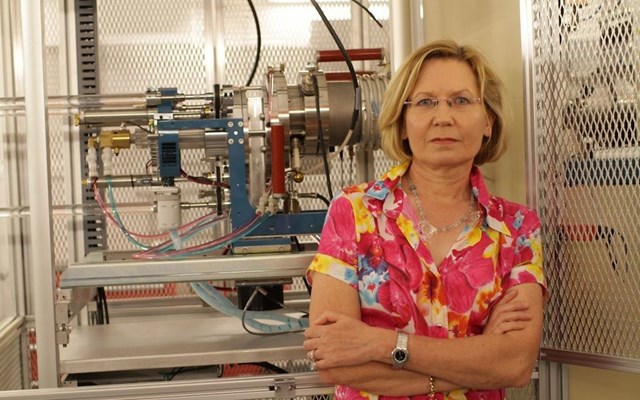

Dr. Elisabetta Boaretto, Head of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s D-REAMS Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory (courtesy)

Archaeologists’ evidence of Israelite settlement in the Land of Canaan and the foundation of a magnificent biblical Kingdom of David is being called into question.

According to a new Cornell University study of radiocarbon testing in the southern Levant, what little organic material researchers have unearthed that was believed by scientists to have originated at the dawn of the Israelite settlement, may not have been dated properly.

Blame it on the weather: The recently published paper, which takes into account Israel’s notably long summers, casts doubt on methods of dating ancient organic materials in Israel, southern Jordan and Egypt.

If the paper’s findings are borne out, the historical timeline of the Holy Land would need to be rewritten.

Through a faulty calibration scale, the study argues, organic carbon-14 evidence linking archaeological sites to the Israelite period may have been given false early dates. This new proposed calculations would cause their “biblical” ties to be much less certain.

To be precise, the study’s findings indicate a discrepancy of only a few decades — but that is just dramatic enough to dispel much C-14-based “evidence” of a potential Davidic United Monarchy.

In his recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) journal, “Fluctuating radiocarbon offsets observed in the southern Levant and implications for archaeological chronology debates,” Prof. Sturt Manning suggests that the current international radiocarbon calibration curve IntCal13 is unsuitable for use in carbon-14 dating in Israel and the region, and can cause dating errors ranging from a mere few years to several crucial decades.

For the past 20 years, a heated debate has been playing out between researchers who use the Bible as a blueprint for archaeological chronology, versus others who claim the evidence speaks to a much more recent settlement, or “Low Chronology.”

If accepted, Manning’s new dendrochronological study of juniper tree-ring records in Jordan and Israel would appear to constitute another point for the Low Chronology team.

Radiocarbon testing was developed as a tool for archaeologists to date ancient organic material in the wake of World War II, by an American former Manhattan Project scientist, physicist Willard Libby. Essentially, when radioactive atmospheric rays hit nitrogen in the atmosphere, their love child is radiocarbon. The isotope, which has eight neutrons and an atomic mass of 14 (thus the C-14), is mixed with oxygen and creates radioactive carbon dioxide, which is then “inhaled” by plants through photosynthesis.

Along the lines of “There Was an Old Lady,” the radioactive carbon dioxide inhaled by the plants is ingested by animals and transported through their bodies. When the flora or the fauna die, the C-14 also begins to decay. The smaller the amount of C-14, the older the sample.

Today, traditional carbon dating is aided by the IntCal13 curve — revised and adopted in 2013. The curve is based on securely dated findings taken from trees, usually oaks or conifers, from the northern hemisphere. And here’s the rub: Anyone who has visited Sweden versus Israel in August, knows that the Mediterranean climate and growing patterns are significantly different — and it’s much, much hotter.

However, this standardized calibration, IntCal13, is used in international testing.

“If anyone does a radiocarbon age measurement on an unknown-date sample – like for example some grains from an archaeological site in Israel – whether run at the Weizmann Lab [in Rehovot] or Zurich or Oxford or Arizona or wherever – then to get a calendar age they use the standard international radiocarbon calibration curve – i.e. IntCal13,” Manning elaborates in an email exchange with The Times of Israel.

“And this was the point of our project – we wondered whether the different growing season in the southern Levant might complicate the use of this radiocarbon record in this area,” explains Manning.

For most carbon dating in the northern hemisphere, the current “corrective” formula is sufficient, Manning argues. Not so in the southern Levant.

“The southern Levant has almost the opposite (antiphase) growing season versus central-northern Europe and northern North America. Thus this issue of a regional offset or need for a regional radiocarbon calibration curve only applies at a significant level in those places, like the southern Levant (and Egypt fits here too), where there are major offsets in growing seasons versus, for example, central and northern Europe,” he explains.

To test his hypothesis, Manning and his team used the Juniper (Juniperus Phoenicea) tree-ring record for the years 1610 to 1940 CE from a site in southern Jordan.

“We analyze 14C levels in known-age native Juniperus phoenicea tree rings across this period, employing a tree-ring chronology constructed from samples from historic structures at Taybet Zaman (TZM) in southern Jordan,” he writes in the article. They measured how much carbon-14 was found in the rings’ annual growth.

Why the juniper? “It is one of the very few tree species growing in the southern Levant for which it is possible to build secure multi-century annually resolved tree-ring records,” he explains to The Times of Israel.

The idea was to find a species which would accurately represent the growing period in the region. Whereas the species the IntCal13 calibration is based on grows from late spring to late summer, most native southern Levant fauna do not.

“A number – but not all – of the crops and plant resources used by humans in the southern Levant and dated by archaeologists using radiocarbon should have growing seasons that are broadly similar to the juniper trees (so autumn to early summer – and especially spring) and hence the radiocarbon record from the juniper trees should be relevant,” says Manning.

The team’s results identified a disparity in the carbon dating which used the IntCal13 curve to a tune of some 20 years during this 330-year test period. In the study, he extrapolates that in even more ancient periods, it could vary even more significantly.

“Over the three centuries for which we have data at present the ‘average’ is around 20 years. But it varies, such that at some periods it is in fact a bit more than 20 years, and at other times it is less and even seems quite small,” he says.

Juniperus phoenicea sample TZM-17 from Taybet Zaman, Jordan (now Hyatt Zaman Hotel & Resort). (Sturt Manning, Cornell University)

A ringing ripple affect

Just how accurate is high-resolution archaeological dating in general? Manning, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Classical Archaeology in the Department of Classics and director of the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory, gives a qualified answer.

“Of course a lot of effort in archaeology has gone into developing high-precision sequences/dating,” Manning says, naming several of the methods. “If you can use dendrochronology [tree-ring dating] directly, then you have an absolute date.”

Combining the use of tree-ring dating with radiocarbon testing, creates accuracy of within a few years, he says, citing a project his lab and colleagues undertook in placing Mesopotamian Middle Bronze Age chronology.

“If you only have radiocarbon but have a good set of data and a known archaeological sequence (e.g. stratified layers at an archaeological site) then you can hope to get within a few decades or so – so high-precision dating,” he says.

And here is the big catch: “If you have nothing but a few radiocarbon dates, then you are more looking at ca. 50-100 years or so precision,” he says.

During the particularly sensitive early Iron Age in Israel, such a broad 50- to 100-year time frame can mean the difference between one archaeological or biblical era and another.

“This is the point of our paper: such accuracy and precision is affected in the southern Levant by our finding of what seems to be a small but relevant, and fluctuating, growing-season (and climate) related offset,” he explains.

For decades, Holy Land archaeologists have put together in-depth, detailed projects with the goal of dating their sites to the early Iron Age in Israel. Heavily leaning on radiocarbon dating, they have arrived at specific date ranges using ancient organic matter. Based on these potentially false findings, says Manning, scholars have then proposed historical and archaeological arguments.

“Our project creates a complication,” he says. A re-calibrated system based on the regional growing period would force the dates several decades into the present.

“This affects claims of high versus low chronologies where the supposed differences are of the order of decades to 50-100 years,” he says.

What’s a couple decades between friends?

For the past several decades, one of the most heated academic debates circles around the question of the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible. Specifically, the dating and chronology of the Davidic United Monarchy.

Historically in this contentious academic boxing arena, foremost in one corner is Tel Aviv University Prof. Israel Finkelstein. In the other, a cadre of archaeologists from Hebrew University and elsewhere.

Israeli archaeologist, Prof. Israel Finkelstein. (Argonauter, CC-BY-SA, via wikipedia)

In 1996, Finkelstein published a paper suggesting the date for the beginning of Israel’s Iron Age IIA be lowered from the High Chronology school’s 10th century BCE to the 9th century BCE.

The crux of the continued Low vs. High Chronology debate is due to “the scarcity of stratified artifacts datable on their own merit to the 11th–9th BCE range,” explains leading Israeli radiocarbon expert, Weizmann Institute of Science Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto, in a 2005 article.

“The discussion has relied mainly on correlations of Iron Age strata with historical scenarios, based mainly on differing interpretations of the biblical text,” she writes.

In the ensuing years, the issue has been slightly sharpened, and Boaretto writes that “the debate now concerns the beginning of Iron IIA — whether or not it should it be placed at about 1000–980 BCE, as maintained by HC adherents, or about 920 BCE, as claimed by LC adherents,” she writes. Basically, a difference of only a few decades.

Boaretto, outlines in a 2015 article why this transition period is such a “crucial moment in history.”

“It documents not only a change in material culture; in the hill country it represents a transformation from a relatively egalitarian rural society in the Iron I to a more hierarchical society, urbanism, and the emergence of territorial kingdoms in the Iron IIA,” writes Boaretto.

In other words, evidence for the transition of tribal Israelites to the Kingdom of Israel.

Based on Manning’s recent findings, which bring the C-14 dates closer to modernity, the Low Chronology school is thrown a proverbial ancient bone.

“If they are right, my Low Chronology dates will be pushed even slightly lower and this may impact certain historical issues. We will test their results on one or two case-studies soon,” says Tel-Aviv University’s Finkelstein.

“This is a very interesting article, which must be given careful attention,” adds Finkelstein.

Bar-Ilan University Prof. Avraham Faust at his Tel ‘Eton archaeological excavation in Israel’s Shphelah region, May 4, 2018. (Amanda Borschel-Dan/Times of Israel)

Other archaeologists are more careful in their analysis of the Manning article. Bar-Ilan University Prof. Avraham Faust, director of the decade-long Tel ‘Eton excavations, recently made international headlines upon the publication of carbon-dating results from two charcoals and an olive pit taken from an Israelite house — late 11th century to the third quarter of the 10th century BCE.

Faust tells The Times of Israel that while the Manning study is interesting and potentially important, “I think it will take some time to see what are the implications of this, and how significant (if at all) it will be in the bottom line.”

Head of the Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology Prof. Yosef Garfinkel is more dismissive. “They talk about variations of up to 20 years, in certain periods only. This is not such a dramatic change,” he writes in a brief email.

Israel’s leading expert weighs in

Weizmann leading radiocarbon-dating expert Boaretto tells The Times of Israel that the Manning study is “a very good push” to open up the potential use of radiocarbon data to fields outside of archaeology, such as monitoring climate and seasonal effects.

Science, she says, is a beautiful dialogue.

Especially in the high-resolution dating of sites in Jerusalem and other sensitive areas in the Holy Land, the difference of a decade or two could change the answer to the questions of “who built this, who destroyed it, and who was here,” she says.

The science, she says, is “moving forward all the time. We never think we know everything. Now we know to look for better analysis,” says Boaretto.

At the same time, she says, “I think it is not the last word. I think this will not be taken ‘as is’ to change the calibration.” More research and data are needed before such a massive shift.

Boaretto points to what she considers a very important sentence in Manning’s article: “Needless to say, this is an approximate and subjective adjustment; the exercise is aimed to be indicative and not robust,” wrote Manning.

Manning tells The Times of Israel that he hopes to put together another study for the southern Levant. “We focus here as it is an area where high-resolution chronology is of considerable interest for archaeology/history and palaeoenvironment studies,” he says.

“The next step – subject to finding funding of course – would seem to be to try to extend the comparison for the southern Levant… over a longer period to demonstrate it better and to increase precision. We hope to do this,” says Manning.

A more complete study is only one part of the picture, says Boaretto, who believes in a 360-approach to archaeology.

“Building a reliable absolute 14C-based chronology requires the integration of different methods both in the field and in the laboratory,” she writes in a 2015 Radiocarbon article.

Academic and field archaeologist Faust couldn’t agree more.

The Manning study “is a good cautionary tale as to why we should never rely on one anchor (especially something from another field) when trying to reconstruct an historical process,” says Faust.

“When we attempt to create large-scale historical reconstructions, radiocarbon dates are simply one component. What is more important is how all the pieces of information fits together,” says Faust.