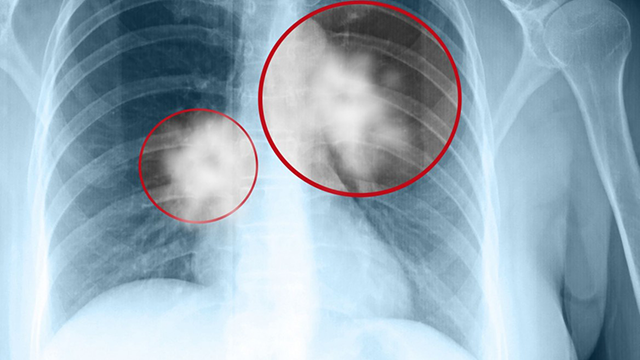

New Israeli approach stops lung cancer cells from developing resistance to chemotherapy in mice.

Photo via www.shutterstock.com

Lung cancer patients know that the statistics for a full recovery are not in their favor, but new research coming out of Israel could alter these grim figures. According to the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Prof. Yosef Yarden, an innovative strategy involving a three-pronged approach might keep an aggressive form of lung cancer at bay.

Yarden and his lab staff showed on mouse models that their approach stops lung cancer cells from developing resistance to chemotherapy.

Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer death worldwide (for men and women) and is responsible for some 1.59 million deaths a year, according to the World Health Organization.

While cancer recurrence is always a worry for anyone who has finished treatment of the disease, studies have shown that if lung cancer returns there is almost no chance of the tumor ever being cured, according to the American Cancer Society. Add to that the knowledge that the recurring cancer is often resistant to the chemotherapy and other drugs that originally drove it into remission.

But the new research by the Weizmann Institute and other scientists, which arose out of some puzzling results of clinical trials, is offering a possible silver lining.

According to cancer societies, some 15 percent of people with non small cell lung cancer have a particular mutation in a receptor on the cell membrane, called EGFR, which can be treated with a sort of “wonder drug.” This drug keeps a growth signal from getting into the cell and prevents the deadly progression and spread of the cancer.

But usually within a year, those with this mutation experience new cancer growth – a result of a second EGFR mutation.

While researchers had tried to administer an antibody drug that is used to treat colorectal cancer and should have been able to effectively block the EGFRs – the growth receptors – including those generated by the second mutation, clinical trials of this drug for lung cancer did not produce results. “This finding ran counter to everything we knew about the way tumors develop resistance,” says Yarden.

Leaving healthy cells alone

In the new study, Yarden and his student Maicol Mancini discovered what happens to cancer cells when they are exposed to the receptor-blocking antibody.

“The blocked receptor has ‘siblings’ – other receptors that can step up to do the job,” says Yarden, who recently published the findings in Science Signaling.

The Israeli team found that when the main receptor (EGFR) continued to be blocked, one of the cell’s communication networks was rerouted, causing the siblings to appear on the cell membrane instead of the original receptor. The finely-tuned antibody did not block these, and the cancer cells were once again “in business.”

“The researchers uncovered the chain of protein communication in the new network that ultimately leads to appearance of the sibling growth receptors. This new network may overcompensate for the lack of the original receptor, making it even worse than the original,” the Weizmann Institute said in a statement.

The team also found that the rewired network sometimes included another molecule, known as receptor tyrosine kinase MET, which purposely binds to one of the siblings. And this signaling molecule is regularly found in metastatic cancers.

Once Yarden, the recipient of the 2015 Leopold Griffuel Prize for Fundamental Research, and his team knew how the blockade was breached, they set out to find a better line of defense.

They created new monoclonal antibodies that could target the two main growth receptor siblings, named HER2 (the target of the breast cancer drug Herceptin) and HER3. The idea was to give all three antibodies together – the two new ones and the original anti-EGFR antibody – to prevent resistance to the treatment.

The researchers tried this triple treatment on mouse models of lung cancer that had the secondary, resistance mutation. In these mice, the tumor growth was almost completely detained. And even more importantly, advanced research showed that this treatment reigned in the growth of the tumor while leaving healthy cells alone.

More research is required before the triple-treatment approach makes it to the clinic, but Yarden is hopeful that it will change the current modus operandi regarding treatment for lung cancer. He also hopes it will further understanding of the mechanisms of drug resistance.

“Treatment by blocking a single target can cause a feedback loop that ultimately leads to a resurgence of the cancer,” he says. “If we can predict how the cancer cell will react when we block the growth signals it needs to continue proliferating, we can take preemptive steps to prevent this from happening.”

Also participating in this research were Drs. Nadège Gaborit, Moshit Lindzen, Tomer Meir Salame of the Biological Services Department, and Ali Abdul-Hai, also of Kaplan Medical Center; and research students Massimiliano Dall’Ora and Michal Sevilla-Sharon; together with Prof. Julian Downward of the London Research Institute, UK.