A revolutionary radiocarbon-dating technique can now securely pinpoint when monumental structures in Jerusalem’s Old City — including the famed Wilson’s Arch — were constructed.

By meticulously collecting organic material in each excavated stratified layer and carbon-dating minuscule samples taken from ancient mortar, an interdisciplinary team from the Weizmann Institute and the Israel Antiquities Authority can now lay to rest abiding debates on when ancient Jerusalem structures were constructed. For a change, scientists are stepping out of the laboratory and into the field.

The specific focus of the project was Wilson’s Arch, which supported one of the main pathways to the Second Temple. It has been dated by three previously prevailing theories of its construction: early Roman (before 70 CE), mid-Roman (1st-2nd century as Aelia Capitolina), or even the early Islamic periods, some 600 years later.

Wilson’s Arch was named after 19th-century British geographer Charles William Wilson who documented the site in a survey of Jerusalem.

According to the results of the new radiocarbon study, Wilson’s Arch was actually constructed in two phases — first around the time of the rule of Herod the Great (circa 37-4 BCE), the bridge was constructed to be 7.5 meters wide. A few decades later in the first century CE, the bridge’s width was doubled to 15 meters.

The reason behind the doubling in size still remains a mystery, IAA archaeologist Dr. Joe Uziel told The Times of Israel.

According to Uziel, the interdisciplinary study is significant in terms of the results of the radiocarbon dating, as well as its methodology’s potential application on monumental structures throughout the Classical world, such as ancient Greece’s Parthenon.

The joint research project between Weizmann Institute scientists and IAA archaeologists has led to the development of a new microarchaeology protocol, Uziel told The Times of Israel, “in order to deal with the situation of amazing architectural structures that are still standing and will be in use for many many years.”

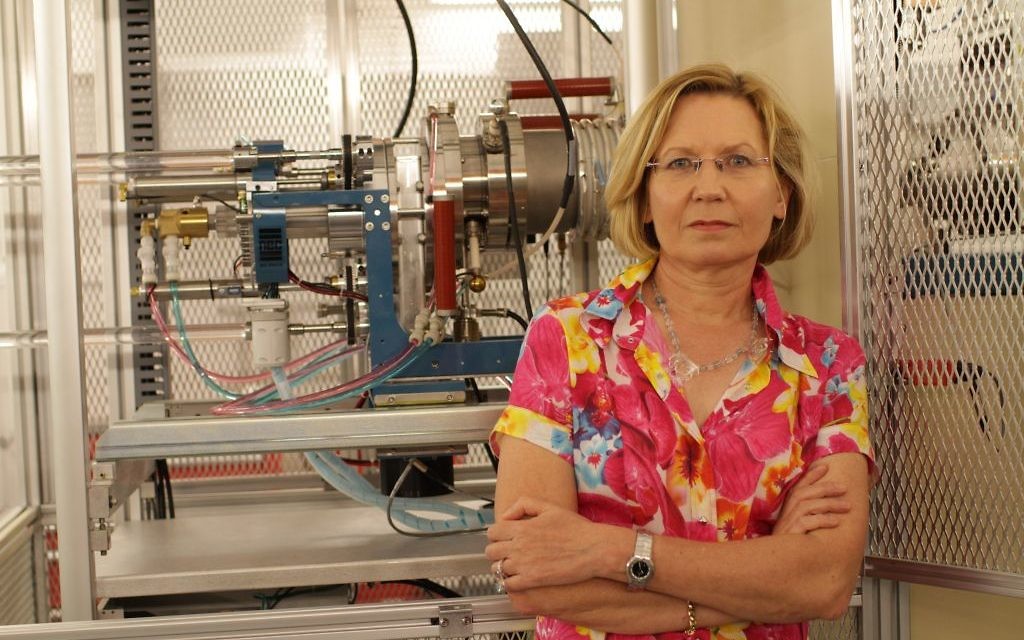

Microarchaeology — the science of looking at the very tiny molecular side of archaeology, usually with tiny samples — is still relatively new and the Weizmann researchers are pioneers in the field. “For this project we had to develop a very specific strategy, starting by being in the excavation, itself,” said Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto in a press release.

“The Wilson’s Arch riddle could not have been solved without the use of micro-archaeology,” said Boaretto. “We showed that the extreme accuracy of our lab results, even for the tiniest of samples, can resolve these issues with a high degree of certainty, and we think they might help solve other archaeological puzzles for which radiocarbon dating had not previously been considered to be sufficiently precise.”

The new field-based techniques were given a test run in an excavation conducted by the IAA’s Uziel, Tehillah Lieberman and Dr. Avi Solomon between 2015-2019 under Wilson’s Arch in the Old City of Jerusalem as part of the development of the Western Wall Tunnels, a major Jerusalem tourist attraction, and to provide a chronological dating for the arch itself. The results were published on June 3 in the academic PLOS ONE journal in a paper, “Radiocarbon dating and microarchaeology untangle the history of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount: A view from Wilson’s Arch.”

Uziel said that while the goal was to find a secure dating for Wilson’s Arch, the dating of the other structures — layer by layer — was hardly a byproduct, rather a new, meticulous archaeological technique.

“The reason [of the excavation] was dating Wilson’s Arch, but the approach was we’re doing this top-down for everything we’re exposing,” he said. “The by-product was that since we were dating every single layer, we were also dating these very important structures, such as Wilson’s Arch,” he laughed.

Updating Jerusalem archaeology

The microarchaeological emphasis of the Wilson’s Arch excavation is part of a broader, multi-year research project to supplement the relatively few examples of carbon dating that have been carried out in Israel’s capital.

“Until today, C14 [carbon-14] has been used rather sparsely in Jerusalem,” said Uziel, and only three secure dates had been collected prior to the launch of the project about four years ago. Uziel said the IAA was approached by Boaretto and Dr. Johanna Regev of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Scientific Archaeology Unit who said, “‘We’ve got to correct the C14 dating situation in Jerusalem.’ So we decided to begin this big project — to set the clock for ancient Jerusalem.”

The partnership has already garnered an additional 45-odd secure dates for ancient Jerusalem constructions through the Wilson’s Arch project, as well as an earlier initial test drive at the Gihon Spring. The project is funded by the Israel Science Foundation and is a collaboration of three field archaeologists, Tel Aviv University’s Prof. Yuval Gadot and the IAA’s Uziel and Dr. Doron Ben-Ami (IAA), together with Weizmann’s Boaretto and Regev.

Uziel explained that whereas other archaeological sites throughout Israel were already including C14 dating in their “tool box,” archaeologists working in Jerusalem were typically more conservative and relied on pottery typing and coins (when available) for dating their sites. The current partnership with the Weizmann team integrates simultaneous fieldwork, stratigraphy and microarchaeology analyses with intense radiocarbon dating from samples taken in situ to create a much more narrow window of time, according to the PLOS ONE paper.

In many “normal” excavations, the studied structures are disassembled, allowing archaeologists to take samples from under the foundation to date them. However, in the case of the Wilson’s Arch area — as well as heritage sites around the world — archaeologists must be noninvasive in their approach. The scientists, working in the field, instead took minuscule organic material from mortar found between stones that was then analyzed in the lab.

An unfinished theater gets new explanation

Aside from Wilson’s Arch, the archaeologists now have new insights into other puzzling structures, including an unfinished theater, which is found below the arch. According to the press release, the radiocarbon dating indicates that the theater’s construction most likely began circa 130 CE, just before the outbreak of the Second Jewish Revolt, aka the Bar Kochva revolt.

Uziel calls the revolt, “a nice historical connection that can’t be proven,” saying prosaically that often buildings stop being built for many other more mundane reasons, such as lack of funds. “But the fact that the dates fit in there well makes it all the more exciting,” he laughed, saying perhaps it will spark a new dating debate.

For Boaretto, the implications of the in-field C14 sampling are broad. “From an arch built by Herod, to a theater complex abandoned before it was completed as a consequence of Bar Kochba revolt, you can take a fresh look at the city’s history and place this monumental building in its proper historical setting. That certainly helps solve this riddle,” she said.

The new methods, said Uziel, “Will be a calling card for future studies dealing with archaeological remains that are still standing, not just in Israel, but it will affect studies elsewhere as well.”