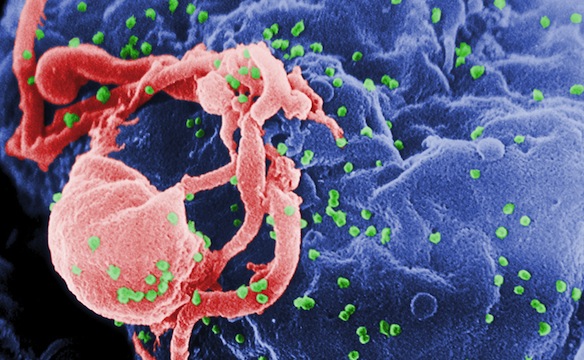

Scanning electron micrograph of HIV-1 (in green) budding from cultured lymphocyte. Multiple round bumps on cell surface represent sites of assembly and budding of virions. Photo by C. Goldsmith

The race to find a cure for AIDS, one of Earth’s most pressing epidemics for more than three decades now, is often more of a chaotic relay. Thousands of international scientists must constantly revise their own projects to keep up with findings from across all scientific disciplines — always collaborating toward a common good, yet also trying to stay one step ahead of the competition.

Israeli biologist Ron Diskin, 36, knows this cycle well. Still, he’s more of a team player than a superstar. Despite his status as a standout in the global AIDS research community for his investigation into the microscopic structure of the HIV virus — and, most recently, his revelations on the human body’s own natural HIV defense system — Diskin is hesitant to hype his individual results.

“I know people want to hear about [a cure], but this is not my research,” said Diskin, sitting in his spacious new office at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. “My research is purely structural.”

The young scientist — who casually inhabits his swivel chair in a pair of khaki shorts, an orange T-shirt and a wide, geometric smile — said that applying his findings to the creation of a therapeutic agent will likely take years, although there are constant reminders that one is needed today.

The Consulate General of Israel in Los Angeles, with financial help from the Weizmann Institute, decided to fly Diskin out for a visit Oct. 10-16 for a whirlwind week of AIDS events and speaking opportunities. These include the annual AIDS Walk Los Angeles — in which Diskin will participate on Oct. 13 — as well as a town hall meeting at Congregation Kol Ami in West Hollywood and a series of more scholarly presentations at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, USC and UCLA.

Of the various paths that scientists are currently forging toward an HIV vaccine, Diskin’s research has provided some of the most stable footing, said Z. Hong Zhou, a UCLA professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics who invited Diskin to speak about his research at UCLA this month.

Diskin was part of a U.S. team which recently identified a group of potent antibodies that grow naturally in some HIV patients after a few years of infection — proteins produced by the patients’ own immune systems to fight off the HIV virus. In 2012 and 2013, Diskin’s team published a series of groundbreaking papers showing that these exceptionally strong HIV antibodies, called “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” could be synthetically reproduced — and even strengthened — in the lab.

Unlike previously studied antibodies, Diskin’s new, more versatile antibodies proved effective against many different types of HIV, including those more prevalent in Africa and Asia, where the AIDS crisis is ugliest. They also stood up to sneaky mutations within the HIV virus over time.

In December 2012, Diskin’s team proved in a paper that these new antibodies could “effectively control HIV-1 replication in humanized mice, and should be re-examined as a therapeutic modality in HIV-1-infected individuals.”

UCLA’s Zhou praised Diskin’s contribution to the breakthrough.

“What is very, very interesting about Ron’s research is that he’s working on the antibodies produced by human cells — a human mechanism of defense,” he said. “Knowing how the antibody [defends human cells] is very important, and Ron basically determined how the antibody binds” to the HIV virus.

The hope, according to Zhou, is that scientists will eventually use Diskin’s research to “design something — sort of a mimic of this kind of antibody — and perhaps use this designed antibody as a vaccine or another therapeutic agent to prevent HIV infection.”

David Siegel, Israel’s consul general in Los Angeles, said stateside visits from Israelis like Diskin are necessary to educate skeptical Americans about Israel’s more progressive side.

“It’s one way to help Israel academically and scientifically, and it’s also a much more proactive way of dealing with Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions [BDS] issues on campus,” he said.

Much as Miss Israel Yityish Aynaw’s recent visit to L.A. drew interest from Ethiopian immigrants and other African descendants in the area — Aynaw was born in Ethiopia — Siegel said he is hoping the Diskin tour will highlight Israel’s social and scientific advancements, as opposed to its widely criticized activity in the Palestinian territories.

In particular, Diskin’s speech at Kol Ami, an LGBT congregation, is expected to attract many interested members of the West Hollywood community, some of them not necessarily connected to Israel, but eager to hear about Diskin’s world-famous HIV research.

After growing up an outdoorsy kid in Jerusalem and receiving three degrees from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, including a doctorate in biochemistry, Diskin flew to the United States for his postdoctoral studies. He worked under Pamela Bjorkman at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, which has been ranked the world’s No. 1 research university for the last three years by Britain’s Times Higher Education magazine.

Diskin had been trained at Hebrew University in structural biology — specifically, in using a 3D imaging method called X-ray crystallography to examine structural differences within families of proteins. But when he came to work under Bjorkman at Caltech, she surprised him with an offer to work on a new project in her lab: HIV.

Initial results were promising. The Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery, a network of scientists, research entities and supporters working to turn myriad HIV research efforts into a tangible vaccine, recognized Diskin as a “Young/Early Career Investigator” in 2010.

During his first couple of years at Caltech, the Israeli biologist used X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of glycoprotein 120, or GP120, the notorious binding protein on the surface of the HIV virus, which allows it to latch onto and infect host cells.

But the HIV research field was turned on its head in 2011, when Michel Nussenzweig, a scientist at Rockefeller University in New York City, discovered how to clone a whole new set of natural antibodies that were developing in some longtime HIV patients — much more aggressive and diverse than the antibodies that scientists had previously been trying to reproduce as therapies.

“The new [antibodies] were so superior to the old ones,” Diskin said. “It was a completely new story. All of a sudden, it sparked the optimism that some vaccine that will elicit those HIV antibodies will work.”

Nussenzweig’s lab reached out to Diskin and the Caltech team for a fateful pairing that would alter the global landscape of AIDS research.

“We were able to get some structural information about the antibodies, and that was interesting,” Diskin said. “But we did something else that was less expected: We had the structural information in our hands, and we realized that we could actually maybe improve the antibody. … That was the first time that had been done in the HIV field.”

Today, Nussenzweig’s and Bjorkman’s labs continue to collaborate on this mission. However, at the height of Diskin’s antibody research last year, the Weizmann Institute began courting the Israeli HIV prodigy back to the Holy Land. He’s now the hottest new addition to the institute’s structural biology department, where he’s opening a lesser-traveled inquiry into a family of deadly, tropical Arenaviruses — such as Lassa fever — currently plaguing millions in Africa and South America.

“I’m still working on HIV — I have open questions and I have things I will study,” he said. “But considering the major forces in the world, it could be very hard to compete on the very hot topics” in the HIV field.

So Diskin is going back to basics as he builds his own lab among the sleek modern buildings and leafy canopies of the Weizmann Institute, laying the groundwork to do what he does best: map the structure behind some of the world’s most deadly viruses.