Weizmann Institute

A longtime donor to the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel wanted to do more. He had his sights set on endowing a chair that goes to new hires at the institute as they set up labs and assemble research teams. But he couldn’t afford the $750,000 price tag, except through a bequest.

That didn’t stop fundraisers at the New York-based American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science. They worked out a plan with the donor to put his name on a chair sooner rather than later. The donor would start by giving $37,500 each year, roughly equal to what the chair would draw annually from a $750,000 endowment. His estate would pay off the full endowment when he died.

Such plans to link donors’ present and future contributions are known at Weizmann as "virtual endowments." Codified in a new book by Steven Meyers, one of the organization’s top fundraisers, they are just one of the ways Weizmann is breaking with traditional fundraising to customize giving.

Weizmann doesn’t run a conventional annual-giving campaign or split its fundraisers among annual-, major-, and planned-giving departments. Five years ago, it scuttled its planned-giving program, creating instead a Center for Personalized Philanthropy, with a focus on blending gifts.

"This is the opposite of hit-and-run philanthropy," says Marshall Levin, chief executive officer of the fundraising group. "We take a look at the lifelong value of a donor and what their lifetime goals are for making an impact."

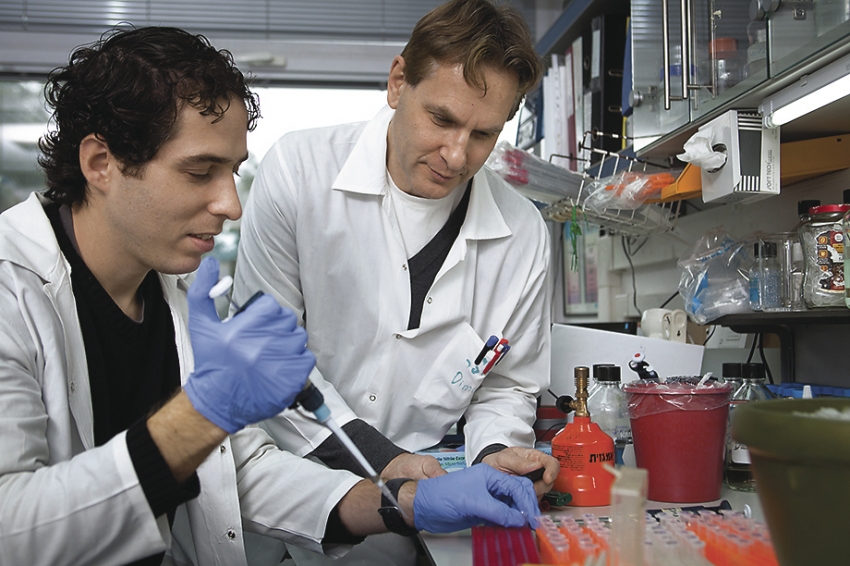

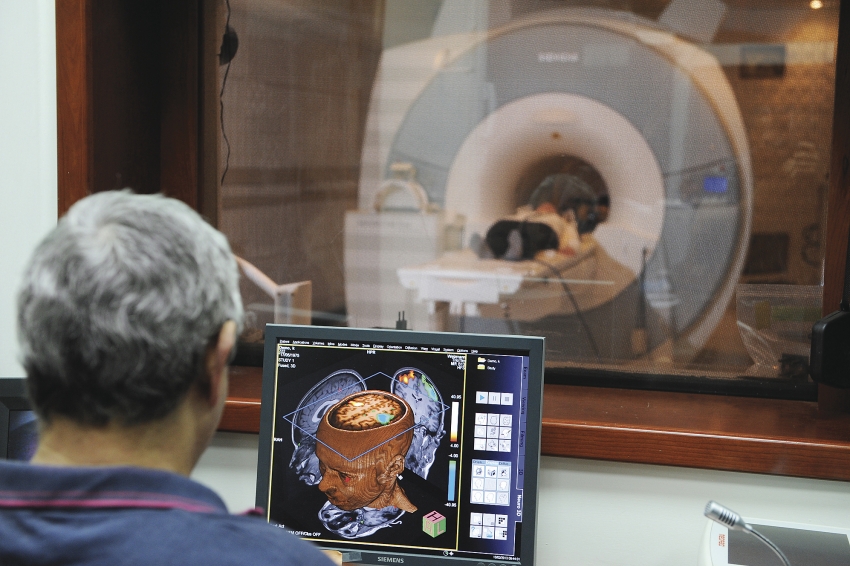

CUTTING EDGE: A Weizmann researcher studies MRI images that show brain activity in real time. The institute's U.S. fundraising arm raises more than $60 million a year.

Rich History

The American Committee was formed in 1944 to support the research university established near Tel Aviv by chemist Chaim Weizmann, who went on to become Israel’s first president. In its 72-year history, it has raised more than $2 billion, averaging more than $60 million a year over the past decade and regularly landing on The Chronicle’s Philanthropy 400 ranking of America’s top fundraising nonprofits.

By a conventional tally of gifts and payments on prior pledges and bequests, the group brought in $74 million in 2014. But Weizmann, taking into account its expanded portfolio, talks internally about a much bigger number: $120.7 million. That total, which the organization considers to be its annual "financial achievement," includes typically non-bookable items such as bequests and the face value of life-income gifts like charitable remainder trusts.

Weizmann is among a small but growing number of charities that have adopted this big-picture calculation, sometimes called "total financial resource development." It’s meant to hew with how donors think about giving. Though many charities treat annual gifts as separate from, say, testamentary gifts, donors are less likely to distinguish among giving vehicles when they consider their overall support for an organization.

Weizmann fundraisers recognize that thinking, giving donors a range of tools and options to use their assets, present and future, to meet their philanthropic goals. The organization typically doesn’t pitch a single gift to its major donors but instead devises a plan to fund the impact they’d like to make. Its website, marketing materials, and fundraisers promote unconventional vehicles like the virtual endowment. The organization even offers what it calls "philanthropic mortgages," through which donors make a series of gifts that cover the spending rate of a chair or program yet also build equity toward a fully funded endowment.

Phil Cubeta, a veteran financial adviser who teaches philanthropy at the American College of Financial Services, says Weizmann officials are using language and ideas familiar to the wealthy and their advisers. "When they talk about the virtual endowment, the philanthropic mortgage, they’re talking about different ways to pay down on an obligation: Do you want to buy it? Lease it? Have a balloon payment?" Mr. Cubeta says. "You don’t usually hear about making charitable donations in those terms or in terms of a spending rate, but it makes sense and gets your attention."

Customized gift options that don’t necessarily require the biggest investment up front are attractive for other reasons. Donors like to dole out donations over time and ensure the money is being used per their agreement, Mr. Cubeta says. And money managers generally like to hold on to their clients’ assets for as long as possible."Wealthy people want more control of their assets, and their advisers want the same thing," he says. "With most charities, advisers might think they are playing defense. With Weizmann, they get to play offense."

Mr. Cubeta uses Mr. Meyers’s book, Personalized Philanthropy: Crash the Fundraising Matrix, in one of his classes. His students, financial advisers, "pick up on the ideas quickly and can’t believe that more nonprofits don’t do business this way," Mr. Cubeta says. "That’s going to change."

Tim Belber, who does generational wealth planning as a principal with the Denver-based Alchemia Group, says he is slowly seeing more donors and nonprofits blending different kinds of gifts. While one charity rejected an Alchemia client’s offer to build an endowment over time, another donor is working with his college alma mater to create a $5 million endowment that would start with annual $200,000 gifts.

"Now my client, the patriarch of the family, says he will be able to have the joy of knowing and seeing the impact his gift will make," Mr. Belber says. "He doesn’t have to wait for a liquidity event, or, if that doesn’t come, his estate to accomplish what he wanted."

From $500 to $5 Million

3 NEW "APPS" FOR GIVING

VIRTUAL ENDOWMENT

Donor commits to a series of gifts that cover the annual spending of an endowed program or chair. A future gift such as a bequest, providing what might be called a "balloon payment" in the financial-services industry, is made to fully fund the endowment.

PHILANTHROPIC MORTGAGE

Donor's annual gift commitment covers the endowed program but includes additional money to gradually build "equity" in an endowment or a legacy fund until it's fully established.

STEP-UP GIFT

Donor establishes a gift at a starting level, then adds to it (usually through a bequest or other balloon payment) to increase the impact. Example: A donor makes a gift to support a master's degree scholarship, then increases it to support a doctoral scholarship or even a professional chair.

Though Weizmann fundraisers are pitching new ways of giving, they haven’t rejected the old maxim that it takes time to build fruitful relationships with donors.

The group’s top 25 contributors gave their first major gift ($100,000 or more) an average of eight years after their initial donation.

One Chicago man in the construction business first gave Weizmann $500 in 2000. Later, as he became more involved, his annual gifts crept into the thousands, and he created a few charitable gift annuities. He participated in events in the Midwest, got to know the regional fundraisers, and, in 2005, traveled with Science at Sea, a cruise trip for donors that includes a flight to see the institute’s campus in Israel.

The following year, he pledged to combine gift-annuity donations with cash gifts of about $200,000 to $300,000 a year to support the launch of a childhood cancer center. In 2008, the donor, who was particularly committed to the cause because he had an adult grandson who had battled cancer as a child, made a $5 million bequest to endow the center. "It was a customized, personalized journey from $500 to $5 million," says Mr. Meyers, vice president of Weizmann’s Center for Personalized Philanthropy. "Because there are no walls between annual gifts and planned gifts and capital gifts and endowment gifts, we all could build a relationship with the donor like it was one extended conversation over the years."

Another old fundraising saw still has currency at Weizmann, according to Mark Feldman, senior vice president of financial resource development: The best prospects are current donors. "We appreciate every contribution, especially because in a life span of a donor you don’t know where things will end up," he says.

Crowdfunding Experiments

To get more donors on the rolls, even at low levels, Weizmann last year began testing small online crowdfunding campaigns supporting research projects in medicine, the environment, space exploration, and other fields. A campaign in November to support brain and Alzheimer’s research quickly raised $12,000 from 38 donors, more than half of them newcomers to the organization.

Though the American Committee is a fairly large fundraising operation, with about 60 employees in offices spread across the country, Mr. Meyers contends its integrated fundraising approach would be particularly useful for small charities. Fundraisers at such groups should be considered generalists – not just, say, annual-giving specialists – who can work with each other and their donors to tap the full potential of supporters’ philanthropy, he says.

Long-Term View of Philanthropy

Mr. Meyers also urges nonprofits to move away from measuring their fundraising efforts solely through a year-to-year accounting of cash received and shift toward Weizmann’s broader, longer-term view of philanthropy, incorporating planned gifts, blended gifts, and the total resources supporters offer over time.

The American Committee may be especially well-suited to operating this way, Mr. Meyers says, as its fundraisers’ approach mirrors that of the Weizmann Institute’s researchers. Both groups are collaborative and measure effort and results over years, if not decades, he says.

Mr. Meyers and other Weizmann fundraisers say the ideas about personalized philanthropy they’ve championed also parallel the institute’s work in the evolving field of personalized medicine, which focuses on finding cures and treatments for patients based on their genetic make-up,

"The same way everyone has a unique fingerprint, everyone has a unique philanthropic fingerprint, a personal philanthropic mission," Mr. Levin says. "It’s our mission to match that fingerprint with the right gift at the right time for the right purpose."