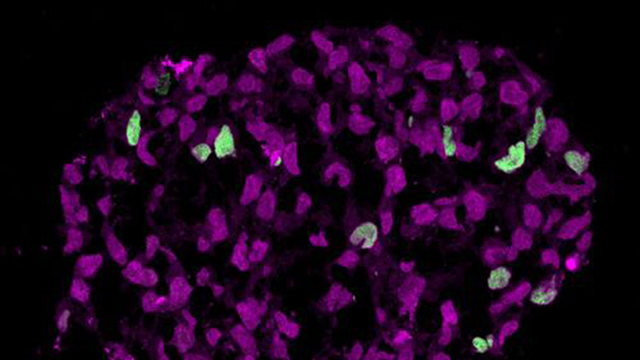

An "embryoid" at the start of the appearance of Sox17 positive cells (green cells), which depict the birth of the human germ cell lineage. (Walfred Tang / University of Cambridge)

Scientists say they have discovered a key factor in the lab formation of human primordial germ cells – the precursors to egg and sperm – and that it differs significantly from experiments involving rodent cells.

In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Cell, researchers at the University of Cambridge in England and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel said their discovery raises questions about how much mouse experiments can tell us about early human cell development.

The research, according to study authors, suggests that "mechanisms of early cell fate decisions in mice cannot be safely or wholly extrapolated to specification events during early human development."

Mouse cells have been used to study primordial germ cells, or PGCs, for well over a decade, and up until recently, the only PGC cells created in the lab were created using mouse cells.

In nature, PGCs arise early in the growth of an embryo, as embryonic stem cells begin to differentiate into basic cells. PGCs become "specified" at this time and will ultimately give rise to sperm or egg cells.

"Researchers have been attempting to create human primordial germ cells in the petri dish for years," said study co-author Jacob Hanna, a stem cell researcher at the Weizmann Institute.

Hanna his colleagues created PGCs by taking human embryonic stem cells – as well as induced pluripotent stem cells – and reprogramming them. By activating some genes and deactivating others, the cells were encouraged to transform into a state similar to naturally occurring PGCs.

In the process of this work, researchers realized that a key gene responsible for the change, Sox17, does not play a critical role in the creation of mouse PGCs.

The use of such lab-formed PGCs may play a critical role in the research of epigenitics – the study of how external factors like diet or the environment can affect gene expression, and how those changes are passed along to offspring.

"Germ cells are 'immortal' in the sense that they provide an enduring link between all generations, carrying genetic information from one generation to the next," said co-author Azim Surani, a developmental biologist and epigeneticist at the University of Cambridge's Gurdon Institute.