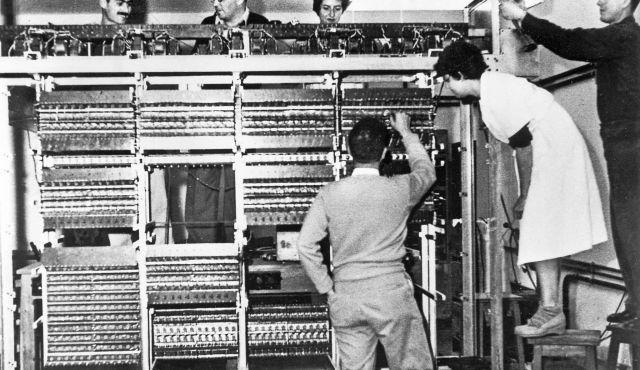

It took 18 months to construct, filled an entire hall and — once functional — became the site of pilgrimage.

The computer under construction. Photo courtesy of Weizmann Institute

In a glass case in the computer sciences building at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, stands a somewhat nondescript item. It’s an old-fashioned machine with lots of wires emerging from it, connecting it to receivers and other electronic components. Only a small sign in the corner reveals its significance.

This is WEIZAC — an acronym for “Weizmann Automated Computer,” the first electronic computer built in the country, in 1954-5 and operational until 1964. It was, the sign tells us, developed in the institute’s applied mathematics department.

Even if it’s hard to imagine this today, WEIZAC is one of the earliest forerunners of Israeli high-tech. Engineers, programmers and mathematicians who were first exposed to the computer at Weizmann became the founding generation of computerization in the country. WEIZAC was the “school” for all those who later planned, built, installed and operated the first computers in the defense establishment, government and industry.

In the early 1950s, at the height of the tzena (as that period of officially mandated austerity was called), the Weizmann Institute invested what was an exceptional sum for the time, $50,000 — a fifth of its research budget — to build the country’s first computer, an adventure whose eventual benefit was not yet clear at the time.

Prof. Aviezri Fraenkel and WEIZAC at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot. Photo by David Bachar

The initiator of the ambitious project was the late Prof. Chaim Pekeris, founder and head of Weizmann’s applied mathematics department. He first had the idea as early as World War II, when he was working for the U.S. Navy at Columbia University in New York, and was exposed to a Bell digital computer. Later, in 1946-1948, Pekeris, who was born in Lithuania in 1908 and came to the United States in 1925 , worked at the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was first exposed to an electronic computer with a logical structure similar to those of today.

“Pekeris worked in Princeton with John von Neumann, the father of modern computers,” says Prof. Aviezri Fraenkel, who was a young engineer on the team that built WEIZAC. “He saw what the computer could do, and when he had problems in applied mathematics that he wanted to solve, he concluded that he needed a computer.”

Therefore, when Chaim Weizmann asked Pekeris, who had arrived in Israel in 1948 , to establish the applied mathematics department, one of Pekeris’ requests was to be able to build a computer.

“There was a committee, which included Albert Einstein, von Neumann and J. Robert Oppenheimer, that helped establish the department,” adds Fraenkel, describing the decisive meeting in 1947 attended by some of the world’s leading scientists, some of whom had a few years earlier worked on the development of the atomic bomb in the context of the Manhattan Project.

“Among other things, the question came up as to whether to build a computer in Israel, because it was a financial issue. They didn’t want to give money so easily for an adventure about which they knew nothing,” he adds. There is one story that says that a dubious Einstein didn’t understand why such a small country needed an electronic computer. According to Fraenkel, “von Neumann, who worked with Pekeris, said that if nobody else would use it, then Pekeris would use it 24 hours a day. That’s not a myth.”

Project WEIZAC finally got underway in 1953, under the leadership of Prof. Gerald Estrin, who had been a member of von Neumann’s team at Princeton. The computer’s construction took only a year and a half — then considered record time — and many people joined the effort.

“The high-tech industry in Israel actually began in Azur,” a small town near Tel Aviv, says Fraenkel. “There was a store there for spare parts for bicycles and fans. That’s where we built the Bakelite surfaces on which the bulbs, resistors and cables were placed.

“The entire computer took up a huge hall,” he continues, explaining that the display in the computer sciences building today is only the core of the computer.

“Next to the hall was a separate building with air conditioning in order to cool. Without cooling everything would have melted,” Fraenkel says of the processor, which was assembled from 2,300 vacuum tubes whose operation disseminated heat. Its memory was four times that of the parallel computer in Princeton — 4 kilobytes, the memory volume of a short e-mail today — at a time when its construction was significantly cheaper than the American computer. The enhanced memory also required redesigning of the Princeton prototype computer’s central monitor.

In October 1955, the daily newspaper Davar reported on the operation of the electronic brain in Rehovot. “After one accustoms the electronic computer to a certain operation, it always knows how to repeat it,” said Pekeris to the reporters present at the launch event. “A complex mathematical operation that would have taken about two days to solve, was solved by the computer within a few minutes. The question that is asked is entered in the form of a 15-20-centimeter tape and the computer is immediately activated — and hundreds of its 2,000 bulbs light up and are extinguished,” said the article.

‘Wanted to use it himself’

Once it was functional, the computer turned into a site of pilgrimage. “They came from all over the country,” recalls Fraenkel, “especially from the defense establishment, which showed up immediately, and even managed to turn some of the programs into operational ones quickly. In other words, it was used for operations in real time.” But computer time was precious, and the various groups competed for the opportunity to work on WEIZAC, he adds: “Pekeris wasn’t happy to give time to other groups. He wanted to use it himself.”

For example, Fraenkel recounts how, “there was a regular hour every week for the defense establishment. Sometimes they wanted a bit more. Pekeris refused to give it to them. They spoke to [David] Ben-Gurion, who was defense minister at the time, he phoned Meir Weisgal, president of the institute, and Weisgal phoned Pekeris. That’s how they convinced him to give the defense establishment a little more time.”

Other groups that used the computer were the Ichud kibbutz movement, the Dead Sea Works, the Israel Electric Corporation, the meteorological service, and of course various departments in the universities. Among the leading scholars who used it were physicist Prof. Yoel Rokach, computer scientist Prof. Amir Pnueli, and economist Don

Patinkin.

The increasing pressure for access to WEIZAC did the trick: “The electronic computer, which was built a few years ago by the applied mathematics department, has been working continously since April 1958, 24 hours a day, without glitches,” said a 1960 article in Davar. “WEIZAC enables the applied mathematics department to carry out many studies that would have been impossible previously: The calculations involved in these studies would have required tens of thousands of work hours by researchers. Today a similar complete job can be done in only hundreds of hours, thanks to the marvelous ‘electronic brain,’ which operates at a speed 250,000 times that of the human brain.”

WEIZAC was finally put out to pasture in 1964. “It started showing signs of age then,” notes Fraenkel. “It was a very reliable computer, but slowly but surely its components started to break down.”

WEIZAC was replaced by the GOLEM computer, which was also built at Weizmann. Fraenkel says that at the time, there was even discussion about having the institute build computers on a commercial basis. In any event, the influence of WEIZAC, he adds, extended long after it went out of use: “There were so many first signs of high-tech that stemmed directly from WEIZAC that I can say with complete confidence that it was the main factor behind the start of high-tech in Israel.”

Dr. Raya Leviathan agrees. She is working on a doctoral thesis about WEIZAC at the Tel Aviv University’s Cohn Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Ideas, and has a doctorate from Weizmann.

“WEIZAC was more influential than is generally thought,” contends Leviathan. “It’s what brought Israel into high-tech. The fact that there was a computer here advanced Israel by quite a number of years. During that period, Israel had no electronics at all,” she explains.

“Computers existed only in developed countries, and Israel wasn’t on the technological level of the United States or the European countries. In 1950, there were five computers in the United States and four in European countries such as England and Germany, where the effort had begun even before World War II. Pekeris wanted to build a computer as early as 1946 [in Israel]. By 1953, there were about 80 computers in the United States, and in the rest of the world there were maybe 20 computers operating or under construction, in Norway, England, Germany, Japan, Canada, France and Holland.”

She claims that WEIZAC’s main influence was to make people realize the importance of the electronic computer and what could be done with its help. “It was a computer that people worked on — as opposed to von Neumann’s computer, which in the final analysis was not used much and was a research tool for learning how to build a computer,” she says.

The difficulty people had at the time in understanding the importance of computers is evidenced in an article, entitled “There’s a brain, but there’s no intelligence,” published in the now-defunct magazine Haolam Hazeh when the first computer was introduced into the Israel Defense Forces in 1961. “The defense establishment has wasted millions of liras on a failed megalomaniacal operation,” said the article.

At the time there was indeed a fear that the computer wouldn’t be used, while today it’s impossible to downplay the importance of the role played by the army in turning Israel into a start-up nation.

“The army was very annoyed that they had to use the Weizmann Institute computer,” says Leviathan. “The Central Bureau of Statistics used WEIZAC for an experiment, and that gave them a push. They brought a delegation of advisers from the United Nations to help them decide how to progress on the subject of computerization. The UN experts recommended that they purchase a used computer from the United States for the army and the CBS, and at the same time build a more sophisticated computer at the Weizmann Institute that everyone would use at the next stage. But the IDF wanted its own computer, and it went for it in a big way. In the end it invested a lot of money in it. Already at the start they planned to have 120 people work on the computer.”

Army applications

Itzhak Amihud, a former IBM employee and the founder of the publisher Hod-Ami, which produces computer books, belonged to the first team of Mamram, the IDF’s central computer unit, which was established in 1959, two years prior to the acquisition of the first computer.

Amihud: “We received our initial training at the Weizmann Institute from Prof. [Philip] Rabinowitz, and we worked on WEIZAC. That gave us a tool to enter this world and to understand how a machine was able to do things that a person thinks about. There was difficulty at the time explaining to people how a machine could think. Today every two-year-old understands the smartphone without any problem. At the time there was a problem in understanding logic and especially long and sequential logic.”

Amihud notes that about 10 soldiers participated in the first Mamram course, and worked on WEIZAC. “They taught us to use software and to understand how to transfer a human being’s logical thinking to a machine. Although there were already machines in the army that used perforated cards, the logic here was on a far higher level,” he says. They used WEIZAC itself mainly for ballistic calculations and intelligence, and when the IDF received its first computer, they also began using it for logistics and manpower systems. But, says Amihud, the soldiers had to be patient.

“It was a very slow machine,” he says, “the computer today in a wristwatch is faster than that computer. The input-output was a machine with a perforated paper ribbon. The program was written in computer codes. One-zero-one-zero. If a mistake was made, the ribbon had to be re-perforated or cut into pieces, and we had to hope that it would pass through successfully. Fixing any mistake in the program was a project, which is why the programs were short and very focused. Each program was a few meters long. The rate of reading was about 10 characters a second. In today’s terms, it would be unacceptable.”

Amihud is a veteran of the founding generation of computerization in the country — someone who was raised on WEIZAC. He served in Mamram until 1963, before joining IBM. As part of his job at IBM, he helped install the first computers at Bank Leumi and at the Israel Electric Corporation. But WEIZAC’s contribution to industry was not only made via the defense establishment. For example, Scitex, one of the great success stories of Israeli

high-tech, which brought computers into industrial use with color printing, was dependent on people who acquired their knowledge of computers working on WEIZAC, including Amir Pnueli.

Hyperlinking the Talmud

Another endeavor that started out with WEIZAC is the Responsa project, which was initiated by Fraenkel. “It’s in effect a Hebrew ‘Google,’ but one that had its start decades before the Google we know today,” is how Fraenkel describes it.

“The Talmud has the equivalent of hyperlinks — in other words, references that connect it to other sources, for example to the Hebrew Bible or later works. In the responsa literature [the body of questions directed to rabbinic scholars, and their answers, from over the past 1,700 years], however, you don’t find such internal references, and this makes it very difficult to use, which is why I thought that a computer could help,” explains Fraenkel.

The initiative, in effect a digital database to more than 90,000 responsa, as well as other Jewish texts, is one of the oldest Jewish software programs in the world, and is still in use in yeshivas, universities and other places, and continues to be updated by Bar-Ilan University. In 2007, it was awarded the Israel Prize for Rabbinical Literature.

“They mocked me. They called me ‘crazy Fraenkel.’ They asked me why I was interfering in things I didn’t understand,” says Fraenkel, who even today, at the age of 84, continues to do mathematical research at the Weizmann Institute.

WEIZAC also won international recognition when it was recognized by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers as the outstanding technological achievement of the 1950s, and its builders received a medal from the institute.

The realization of the importance of government investment in research and technological infrastructure proved itself over the long term. Sixty years after WEIZAC, high-tech is Israel’s main export industry and one of its principal growth engines. Investors and senior executives from all the major technology companies worldwide come to Israel to seek innovative and groundbreaking startups and technologies. And yet, whereas the young country invested in technological and research infrastructure, today government budgets for high-tech companies are shrinking.

“The realization of what a computer can do came only thanks to WEIZAC, otherwise it would have taken several more years,” sums up Raya Leviathan. “In India, which was in a situation similar to ours, computers arrived much later. A computer was very expensive and it was hard to understand what it does. But anyone who tried became addicted, and realized its power.”

Click here for article.