Back from Caltech and the good life in America, Prof. Oded Aharonson is now working on Israel’s first moon shot.

Prof. Oded Aharonson in the observatory at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Nov. 26, 2015. Credit: Eyal Toueg

Prof. Oded Aharonson had a comfortable life in the United States, to which he had moved from Israel when he was 13. At 21, with a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in physics from Cornell University, he returned to Israel for two years to serve in the Israel Defense Forces. At 23, he began his Ph.D. in physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As soon as he completed his doctorate he started working at California Institute of Technology in planetary science, his area of specialization.

The close cooperation between Caltech and NASA allowed Aharonson to be involved in most of the U.S. missions to Mars, he says. “It was my baby.”

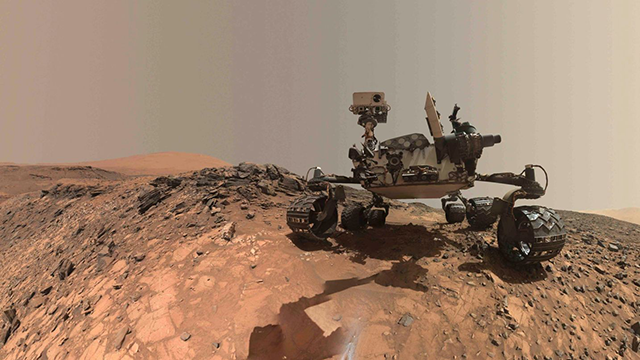

Aharonson was a senior member of the Mars Exploration Rovers’ science team. The vehicles, which NASA sent at a cost of $1.2 billion and which recently found apparent evidence of water on the red planet. Aharonson says that to simplify matters, he often just says he was “the driver of the Mars rovers.”

Aharonson brought all his enormous knowledge and experience back to Israel, when he was appointed the head of the newly established Center for Planetary Science at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot in 2011. He is determined to make it an active part of international efforts to crack the secrets of the universe.

“The rovers landed on Mars in 2002, and since then there is a team that receives the pictures from them every day, looks at them and argues: ‘Is it worth photographing this part, that mountain.’ Every scientist has his own agenda and you need to reach a decision. This is not one meeting a day, but a series of meetings, at the of which a mission plan is formulated. My job was to take that plan and along with the engineers translate it into the language of the rover in order to send the orders that would help the rovers drive, photograph, send data – and do the same thing the next day.”

For almost a decade Aharonson “drove” the rovers on Mars, until he felt he needed to return home.

“I had a wonderful job, tenure, a house and a car, but I felt that all the people I cared about, and who cared about me, are in Israel.”

An artist's rendering of a sun storm around Mars. Credit: AFP

While he was thinking things over – “because it meant giving up a lot” – he took a business trip to Moscow. At one point he went to a restaurant with a Russian colleague.

“He looked at me and said: ‘All of your friends are very focused on their joy, on the question of what will make them happy, but it’s possible to look at happiness a different way: If you go to Israel, another physicist will come and drive the rovers, because at Caltech there are many talented people; but if you remain in the United States, whatever it is you would do in Israel won’t happen.’ This was a Soviet perspective, not personal but general rather. He didn’t measure my value by my level of personal happiness, but by the effect on the state; I, wanting to advance the area of planetary sciences in Israel so that Israel can become involved in a field that doesn’t exist, recognized that he was right.”

Four years down the road, Aharonson says that while he sometimes misses the comforts of the United States, but is happy about his decision to return, moving in the opposite direction of the “brain drain.” Aharonson is 42, unmarried and living in Tel Aviv.

“Maybe I won’t have one-time opportunities to control spacecraft on Mars, but here there are other one-time opportunities,” he says.

Not at a billion dollars per project.

“Our scale is $50 million, projects that are not small but are small relative to the big NASA missions, and are nonetheless a breakthrough in the well-known Israeli method – smaller, cheaper, faster.”

Selfie on the moon

Aharonson’s flagship project is the establishment of the planetary sciences center at Weizmann. He is also the mission scientist on the SpaceIL project to land the first Israeli spacecraft on the moon. SpaceIL is a nonprofit organization established to compete in Google Lunar XPRIZE, a $30-million competition to land a privately funded robot on the moon. Google is offering a $20 million prize to the first nongovernment team to land an unmanned spacecraft on the moon, have it travel 500 meters on the lunar surface and transmit high-definition images and video from the moon. The original deadline of December 2015 has been extended to the end of 2017.

Asked if SpaceIL will succeed, Aharonson says “certainly,” and explains why. Of the more than 30 teams from throughout the world that entered the competition, 16 remain. Israel is leading in many ways and the team has a launch contract that has been approved by Google, which is very important, he says.

“We have a budget that allows us to sign a commitment for a launch, one of the hardest tasks in this process. We still need to build a spacecraft and it needs to work there. You must understand that we are not doing it for the $20-million prize,” explaining that it will cost around $50 million to put the Israeli robot on the moon — all from donations.”

Why is the project important?

“It was launched with the goal of inspiring people in Israel, mainly young people, to study science in order to reach the stars, what we call the ‘Apollo effect’ – the rise in the number of science students as a result of NASA’s Apollo project. The spacecraft is a means to raise awareness, so before I joined they told me, ‘We reach the moon, take a selfie and send it to the new plans.’ Despite the public importance, I thought that a selfie wasn’t enough, and a scientific experiment was needed. It’s important that the Israeli spacecraft reaches the moon in order to learn something new about it, in order to expand the intellectual horizons of humanity, in order to create knowledge we didn’t have before. This thinking, which was accepted by the others, changes the essence of the mission. It is more than just building a spacecraft – we aren’t just planting a flag, but providing a service to science.”

A difficult process of brainstorming led to a decision to measure the magnetic field of rocks on the moon. “Understanding the magnetic field, which is for now a mystery, points to processes that happen in the solar system in general and also the earth. True, it is not practical knowledge for now, but rather basic science, because you never know where it will lead.”

A low-angle self-portrait of NASA's Curiosity Mars rover taken August 5, 2015 and provided by NASA October 8, 2015. Credit: Reuters

As opposed to astronomers, your approach leans toward a type of applied, practical science, even if it’s far in the future. You concentrate on studying planets.

“My motivation is understanding the universe. I have a thirst to understand the cosmos. This is basic curiosity, and the answer to it is basic science. Nonetheless, it seems there is no life on distant stars but there can be life on planets. These are places where it’s possible to imagine humans, or other life forms, living. Our research tries to answer the bigger question when talking about the universe – are we alone? Is there other life around us? Was the creation of life a one-time phenomenon, or is life formed every time the right conditions exist? Are we unique, because it happened once, or perhaps the universe is teeming with different and varied life forms?”

The Center for Planetary Science at Weizmann was established with the support of President Reuven Rivlin, who found a generous donation for it. “Students who want to study planetary science in Israel know that Weizmann Institute is the place,” says Aharonson.

Through the center, he is starting a new project to put Israel on the map of world space research: participation in the European spacecraft going to Jupiter. This spacecraft needs an atomic clock, and the Israel Space Agency decided to support building the atomic clock for the project. “A great achievement because we are part of the scientific team that will learn something new about Jupiter,” he says.

What’s next?

“We submitted a proposal to NASA for an Israeli-U.S. collaboration, involving NASA, Caltech, Weizmann and the Israel Space Agency, on building a satellite to discover exploding stars. This project will cost $100 million, and the satellite will have a camera to photograph the explosions so that telescopes on Earth can be aimed at them to study them.”

Why should a country like Israel invest in breakthroughs in space?

“Space technology has practical use for Israeli power. We will be stronger as a society if we provide incentives for the younger generation to aspire to higher places. This is a real advantage compared to incurious societies, which block intellectual development. This is the time to take the satellites we know how to build, which study the Earth, and turn them upward, to the stars.”