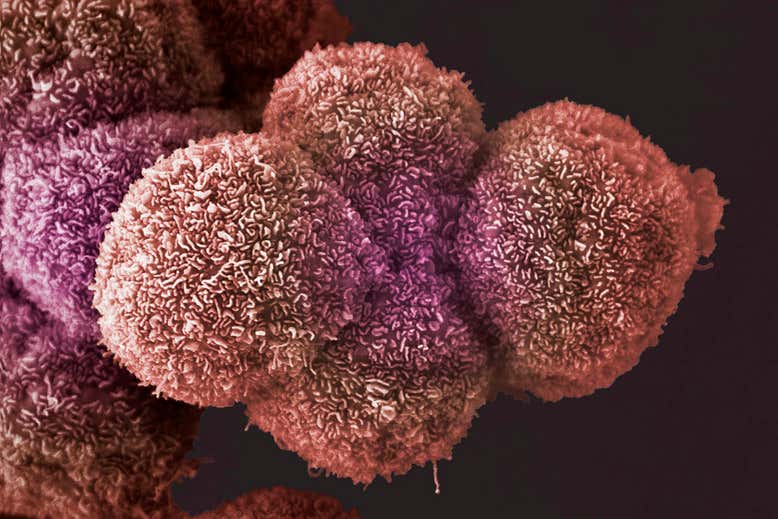

The first comprehensive survey of the microorganisms that live inside tumours has found that bacteria reside in those from many different cancer types, but it is unclear whether they contribute to tumour growth.

These bacteria make up part of a tumour’s microbiome – the complex community of bacteria, fungi and other microbes that live inside it.

Bacteria have previously been found in tumours in the bowel and other tissues in the body that are routinely exposed to microbes. However, less is known about their presence in tumours from other cancers, like those of the bone, brain and ovary.

To get a fuller picture, Ravid Straussman at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and his colleagues looked for bacteria in just over 1000 tumour samples collected from people with cancers of the bone, brain, ovary, breast, skin, pancreas or lung at nine medical centres in four countries.

They found bacteria in tumours from all cancer types, although to differing extents. More than 60 per cent of bone, breast and pancreatic tumours tested positive for bacterial DNA, compared with only 14 per cent of melanomas.

In total, 528 species of bacteria were detected in the tumour samples. A different mix of species was found in each tumour type, with those from breast cancer harbouring the most diverse range of bacteria.

It is unclear why different bacteria colonise different tumours, but exposure to environmental factors that cause cancer may be one factor, says Straussman. For example, the study found that lung tumours in smokers tended to contain bacteria that break down tobacco chemicals.

At this stage, we don’t know why bacteria exist in tumours. Bacteria may contribute to tumour growth, or they may simply find it easier to invade tumours, says Straussman.

If bacteria do play a role in tumour development, we may be able to treat cancer by manipulating the tumour microbiome, he says.

Altering tumour bacteria may also improve the way people who have cancer respond to existing cancer therapies, says Straussman. His team has found that specific bacteria alter a tumour’s response to immunotherapy, which is a common type of cancer treatment.

“We thus envision that a better understanding of this cross-talk between tumour bacteria and tumour immunity will be harnessed in the future to optimise immunotherapy,” he says.

Journal reference: Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.aay9189