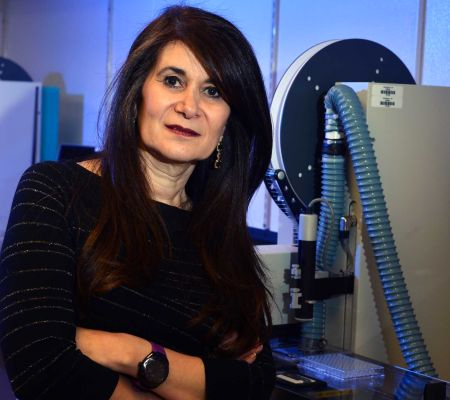

Leemor Joshua-Tor in her Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory facility on March 18, 2014. She is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Credit: Newsday / Audrey C. Tiernan

Leemor Joshua-Tor caught the scientific world's attention in 2004 when her gene-silencing discoveries contributed an important clue in the fight against viruses and diseases such as macular degeneration and cancer. As a principal investigator, she defines research projects and then must figure out how to fund them.

In a shrinking field, she remains competitive. Last year, federal budget cuts meant 1,000 fewer scientists were funded by the National Institutes of Health, according to a University of Pittsburgh study. Yet, in addition to winning NIH funding, Joshua-Tor is one of about 300 scientists in the country funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

She spent a year at Great Neck South High School on the way to earning her doctorate at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and has been at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory since 1995.

Can you describe your latest research?

My last discovery was the particular protein that carries out this whole critical event in destroying RNA. We really want to understand how this works . . . It's like a little missile. You can get very, very specific about what exactly you want to destroy. For example, if you have a virus that infected your body, you can make a piece of RNA that would be directed [only] to the virus.

Why did you choose Long Island for your work?

Several things attracted me to Cold Spring Harbor. It's a very intense research environment, very no-nonsense . . . and it's also near Brookhaven Labs, which has a synchrotron that produces very powerful X-rays, which is important for my experiments.

What have you learned from managing your own lab and researchers?

When I started my lab I always expected them to be sort of like me, but everybody has a completely different way of doing things, and that was my first lesson. If you are able to tune your reactions and the way you interact with them to their own personalities, then you get the most out of them.

What's your biggest headache?

Whether my fellow citizens would continue to understand how important it is to keep U.S. scientists at the forefront in the world. China, India, all these other places are learning from us how to invest in science and learning from us how to do it right. And we're kind of going a little bit backwards . . . We have to keep our edge in this country. It leads to amazing things – technology, biotech, all these things.

Sometimes it takes years of repetitious research to make a discovery. How do you keep it interesting?

The rush of seeing an [important] protein for the first time is unbelievable. You look at the pictures, you realize what it does and how it does it, and for a little while you're the only one who knows it. It's addictive.

What does it mean to run your own lab?

You decide on a scientific problem that you want to go after. You find the place that will give you a bit of space and a good environment to do it in. And then you have to go and raise money – usually from either federal funds or private foundations, hire people; you have a budget. . . Your output are your publications and the results of your study that you send out to the world, hopefully for the benefit of mankind.

You're one of about 300 scientists funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. How do you make a grant application compelling?

It has to be cutting edge. It has to be something that's in the forefront of science. Then you have to convince them that you are the person that should be doing this. . . . you have to be fairly inventive about what you're going to go after.