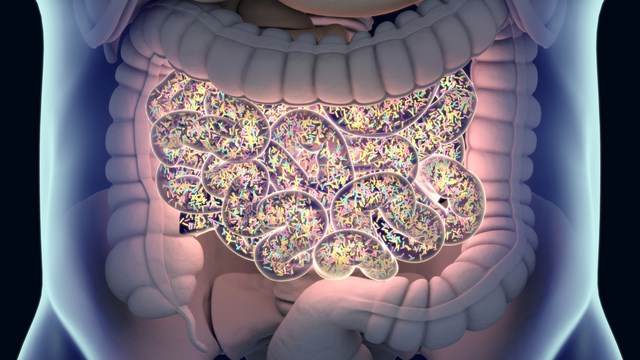

ISTOCK, CHRISCHRISW

Environment plays a much greater role than host genetics in determining the composition of the human gut microbiome, according to a study published today (February 28) in Nature. And including microbiome characteristics when predicting people’s traits, such as cholesterol levels or obesity, makes those estimates more accurate than only personal history, such as diet, age, gender, and quality of life, the study finds.

“For years we’ve been constantly told . . . that the environment in the microbiome may play some role, but it’s kind of minor,” says Jack Gilbert, a microbiologist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the study. “We now see that yes, genomics plays a minor role in shaping the microbiome. The fact that environment has a much bigger role in driving the microbiome than genetics pinpoints the fact that the environment is playing a much more fundamental role in influencing disease onset and disease progression than genetics is.”

The relative influence that host genetics or environment has over the composition of the microbiome, and the effect of the microbiome on disease, have been debated in the scientific community. To investigate this question, Eran Segal, a computer scientist and computational biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science and his colleagues collected blood and stool samples from 1,046 Israeli adults of Ashkenazi, North African, Yemenite, Sephardi, and Middle Eastern descent, as well as some from other origins.

“We had the luxury of doing this study in Israel, which for distinguishing genetics from environment is actually an ideal place,” says Segal. The relatively recent immigration of genetically diverse populations of Jewish people to Israel, where they share a common environment, created the perfect conditions for comparing the degree to which environment and genetics shape the microbiome, he explains. “In Israel this experiment was naturally done for us,” he says.

They compared the host genetic profiles and the diversity between microbiome samples, or ß-diversity, and found that ancestry was not significantly associated with microbiome composition.

“The hosts’ genetics determine a very small fraction of the variability that we see across the microbiomes of people,” says Segal. “We’re not saying that genetics has no effect on the microbiome, but that effect seems to be very small.”

Segal and his colleagues also analyzed an existing dataset from a 2016 study of microbiome composition from 1,126 pairs of twins to determine whether the human gut microbiome can be inherited. From this they determined that between 1.9 and 8.1 percent of the human microbiome is heritable.

“It’s really consistent with what we found,” says Emily Davenport, a microbiologist at Cornell University who was not involved in this study. Davenport was a coauthor of the 2016 twins collection, which found between 5.3 percent and 8.8 percent of gut taxa was inherited. “Certain bacteria are heritable, but it’s a very small portion of the microbiome, and even if we do identify them as heritable, it’s very moderate,” she says.

To examine the degree of environmental influence on the microbiome, Segal’s group also looked the microbial compositions of related individuals who had never lived together, and those of unrelated couples who had shared a household. They found that the microbiomes of relatives who hadn’t lived together were not similar, while those of unrelated couples who lived together were.

Lastly, Segal’s group examined what fraction of host phenotypes can be inferred from microbiome composition. They found that using human genetic data together with microbiome profiles significantly improved how accurately they could predict human phenotypes, compared to using genetic data only. For instance, after accounting for environmental and genetic factors, the microbiome contributed to 36 percent of the variation between people’s HDL cholesterol levels and 25 percent of the variation in their body mass indices (BMI).

Gilbert says the finding demonstrates that the combination of genetics, environmental exposures, and the microbiome is a much stronger predictive toolkit than using any one of the three factors alone. “It’s a call to arms to add the microbiome to those predictive elements,” he says. “Ignore the microbiome and your predictability goes down dramatically.”

“Having an understanding of which bacteria are and aren’t [heritable] is going to be super important if you’re thinking about using the microbiome as a therapeutic and targeting it to treat disease,” says Davenport. “If you’re trying to target a [taxon] that is determined by host genetics, it may be harder to change its abundance.”

D. Rothschild et al., “Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota,” Nature, doi:10.1038/nature25973, 2018.