Illustrative photo of a doctor with a cancer patient (via Shutterstock)

Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have found that diversity in cancer cells causes the cancers to be less responsive to immunotherapies — treatments that harness the immune system to tackle the devastating disease.

The Weizmann researchers say their findings indicate that heterogeneity of the cancer cells should be taken into account when trying to understand whether a patient will benefit from immunotherapies.

The study has shown that “tumor hetereogeneity plays an extremely important role in predicting if patients will respond to immunotherapy,” said Prof. Yardena Samuels of the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department in a phone interview.

The greater the genetic diversity of among the cancer cells, the less likely the patient will respond to treatment, the study shows.

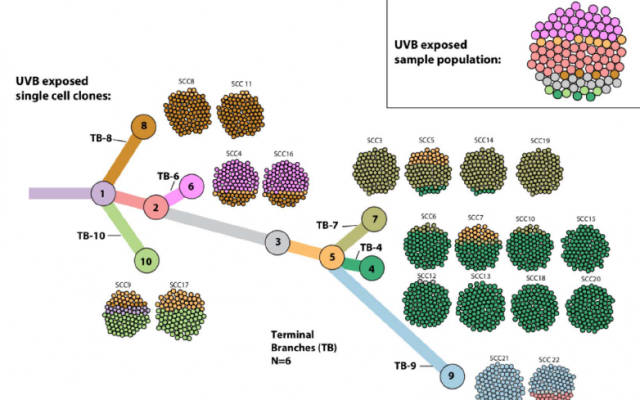

A cell tree (Weizmann Institute)

Immunotherapy treatments — when the body’s own immune system is used to control and eliminate cancers — are drugs that have been developed over the past few years and are considered to be revolutionizing cancer treatment. Unfortunately, not all patients react to these treatments, so researchers globally are on the hunt to improve the drugs and find out why.

One leading hypothesis as to why, supported by a few studies, has been that tumors with more mutations — a higher “tumor mutational burden” — are more likely to respond to immunotherapy. So today, one of the biomarkers doctors use to assess whether patients will respond to immunotherapies is the presence of more mutations of tumor cells.

Now, the Israeli researchers say that their study shows that the mutational load of tumor cells remains an important biomarker, but it is not enough.

“An additional biomarker should be added,” Samuels said. “And that is tumor diversity.

“We need to combine the two biomarkers to derive a score and predict which patient will respond to immunotherapy,” she said.

The Weizmann study shows that when the tumor cells are genetically different from one another, the immune cells — called T cells — make their way to the right area but remain “stuck outside the tumor,” and don’t manage to enter its core, said Samuels. “We don’t know why this is.”

In addition, the study also found that when there is more diversity among cancer cells, there are more suppressor T cells — cells that suppress immune activity, said Samuels.

The findings of this research, which were published Thursday in Cell, may provide better tools for designing personalized protocols for cancer patients, as well as pointing toward new avenues of research into anti-cancer vaccines, the Weizmann institute said in a statement.

Illustrative image of a research lab (Shutterstock)

In the study, led by doctors Yochai Wolf and Osnat Bartok in Samuels’s lab, the researchers took mouse melanoma cells and exposed them to a type of UV light known to promote this cancer. This increased both the mutations and the cell heterogeneity in the growth.

When they injected mice with either these cells or the regular melanoma cells, the irradiated ones multiplied faster and were more aggressive. Despite the fact that these cells had a higher mutational burden — and thus should have been more responsive to immunotherapy — they actually were less likely to be eradicated than those from the original tumor. In other words, although there was a high mutational burden, there was also high heterogeneity, and the researchers hypothesized that the latter was driving the resistance.

Since mutational burden and heterogeneity generally go hand in hand, the researchers needed to find a way to study one without the other. They removed single cells from a culture of an aggressive cancer growth and then grew new cultures from each cell. Thus, they ended up with 22 new cultures, each with a low level of heterogeneity but carrying some random number of mutations.

When they injected these cells into mice, the researchers found that all the tumors grew slowly, and even disappeared without immunotherapy — in those with higher and lower mutational burdens alike. To see if the mice’s immune systems were, indeed, responsible for killing the cancer cells, they repeated the experiment in mice with weakened immune systems. In these, the cancer spread rapidly.

To further understand the immune response, the researchers tried the experiment again, this time on mice specifically engineered to lack T cells — the immune cells that are known to fight cancer. “The results were similar to those in mice with weakened immune systems,” said Wolf in the statement. “When we look at T cells from different tumors, we found much more activity in the homogenous growths, and less in the heterogeneous ones.”

In fact, the researchers found that in the homogeneous growths, T cells had penetrated to the center of the tumor, while in the heterogeneous ones, they remained on the outside, and there were more of the unhelpful suppressor T cells.

“Ultimately, we intend to use the experimental system we created to work on developing applicable personalized protocols for cancer patients,” said Samuels.

Also participating in the research were Prof. Eytan Ruppin of the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of the US, Prof. Lea Eisenbach of the Institute’s Immunology Department, Dr. Yishai Levin of the Nancy and Stephen Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine at the Institute, Prof. Martin Miller of the University of Cambridge, Prof. Eli Pikarsky of Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Prof. Arie Admon of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and Prof. Charles Swanton of University College London.