Weizmann Institute’s Prof. Zelig Eshhar holds a board that illustrates how the cancer treatment works with mice. Aug. 29, 2017 (Shoshanna Solomon/Times of Israel)

Weizmann Institute’s Zelig Eshhar’s genetically engineered T-cells are at the heart of Kite Pharma’s $12 billion acquisition

Prof. Zelig Eshhar’s phones haven’t stopped ringing since the news broke two days ago that Israeli-founded Kite Pharma would be bought by US pharma company Gilead Sciences Inc. for a whopping $12 billion.

Eshhar, a researcher at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, developed the technology which is at the heart of Monday’s acquisition. He is also on Kite’s scientific advisory board, and was one of the first people to get a call from Kite CEO and founder, Israeli-American oncologist Arie Belldegrun, after the deal was signed.

“He called me and said: You are the first one I am telling” about the deal, Eshhar said with a chuckle. “I was very happy.”

Friends, reporters and colleagues have been calling Eshhar ever since to request interviews, offer congratulations, and chat.

“I have been speaking on my phone for two days. I am not used to this. It tires me out. Do you know how to shut this thing off?” he asked, handing this reporter his cellphone.

The 76-year old Eshhar works out of an office in the basement of the Wolfman Building at the Weizmann Institute’s leafy campus in Rehovot. He has pictures of his grandchildren on a shelf. On the walls are a whiteboard with drawings of cells, and the framed awards he has garnered over the years, including the Israel Prize he received in 2015. There are also boards with images of mice with cancer that illustrate how tumors shrink gradually after treatment with his breakthrough technology, which genetically engineers cells to make them fight cancer.

During his studies at a variety of institutions including the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Weizmann Institute and Harvard Medical School, he focused his attention on the field of immunology and cancer.

T-cells and antibodies in patients and animals are part of the immune system, capable of distinguishing tumor cells from normal cells. These cells, however, are not enough to fight the cancer cells, which manage to “evade and avoid them,” he explained. The end result is cancer and an immune system that is not efficient enough to thwart it.

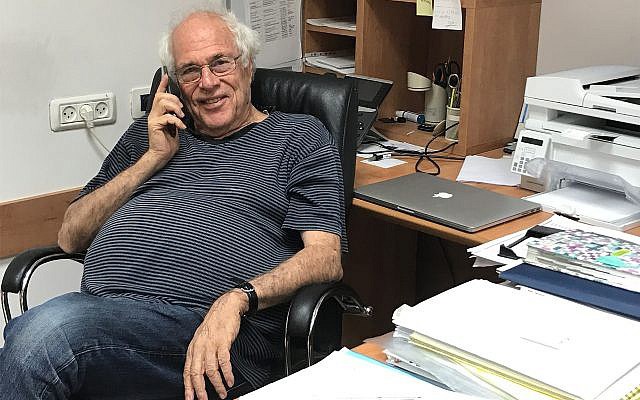

Prof. Zelig Eshhar in his office at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Aug. 29, 2017 (Shoshanna Solomon/Times of Israel)

Eshhar’s eureka moment came when he decided to combine the antibodies with the T-cells, he said: “Two are better than one.”

So he extracted the T-cells and genetically engineered them to include a molecule that has the cancer recognition skills of both the antibodies and the T-cells. The modified T-cells are then injected into patients.

These T-cells “now recognize the cancer and will now be efficient because I engineered them so they will attack the cancer. And that is what we call Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CAR),” he said, drawing the images of a mouse and a rabbit and cells and all their connections on a white piece of A4 paper to better make his point. When put into patients the cells will be “very effective” because they will have the two elements that recognize the cancer and can reject it. “That is all the trick. This is what Kite is using.”

These genetically engineered T-cells have been shown to effectively kill human tumor cells in both animals and humans. But Eshhar’s research is focused on animals.

“I am a PhD and a doctor of mice,” he said with a smile.

Belldegrun acquired the rights to the technology from Eshhar’s private company in 2013 for some $375,000 for Kite, which he founded in 2009. Israeli financial paper TheMarker said that Eshhar’s company is expected to get some $3.9 million from Kite and further milestone payments and royalties from the sale of any of the products developed. The paper said that the Weizmann Institute is expected to get just a small part of these payments, after it agreed years ago to sell back to Eshhar’s firm the rights to his patents.

“I am not a banker and I don’t know the laws,” Eshhar said in response to a question about the money he is expected to make. “I don’t know how much we will get. I prefer not to relate to this. Research is what interests me, to improve the treatment and make it more effective.”

A spokesman for the Weizmann Institute declined to comment.

Eshhar has been continuing his work with his team at the Weizmann Institute — although because he is short of funds at the moment, his team is now down to four to six people, he said. He also works in immunology at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center.

His team at the Weizmann lab is now working on refining the technology and making CARs for more unique, less common tumors, he said.

“We want to improve their specificity to certain kinds of cancer,” he said. “The hard part is to make sure that the cells target only the cancer cells, and that is not yet the case for most cancers,” he said. The key is to refine the technology to make sure that it specifically targets the cancer and not the patient’s normal tissue.

Prof. Zelig Eshhar’s office at the Weizmann Institute of Science. The whiteboard has an image of a mouse and cells. (Shoshanna Solomon/Times of Israel)

His team is also working on developing CARs for other purposes, and not just cancer, he said. “We recently designed CARs against antigens of auto-immune diseases, when the body starts to work against itself,” he said. One target is lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks healthy tissue.

“We make T-cells that don’t kill, but suppress the reaction,” he said. His team also made CARS against rheumatoid arthritis antigens to alleviate the disease, he said.

Does Eshhar believe immunology is the way forward to treat cancer?

“I like it because it is my baby,” he said. People will continue to use radiation and medicines to fight tumors, he said, but immunology “is one way to overcome many problems to make it specific.”