Technology employed by US researchers to help leukemia patients, hailed worldwide this week as potentially ‘extraordinary,’ was originated by Weizmann Institute’s Prof. Zelig Eshhar

Illustrative photo of a doctor with a cancer patient (cancer patient image via Shutterstock)

A breakthrough cancer study in which patients suffering from a form of leukemia saw their diseases go into remission after they were treated with genetically modified T-cells has deep roots in Israel.

One of the first in the world to work on the innovative adaptive immunotherapy technique to treat cancer, which was hailed Tuesday worldwide as a potentially “extraordinary” development, was Weizmann University Professor Zelig Eshhar. Speaking Wednesday on Israel Radio, Eshhar said he was very heartened to hear about the results of the study at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I’m not surprised to hear about the results,” he said. “In our lab, we cured many rats and mice of cancer. I have been saying for years that we could do this in people, as well.”

In an article in the journal Science Translational Medicine, a team at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center and the Perelman School of Medicine reported that 27 out of 29 patients with an advanced blood cancer saw their cancers go into remission or disappear altogether when they received genetically modified T-cells that were equipped with synthetic molecules called chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs. Those T-cells were able to target and destroy the tumor cells – specifically the ones that were responsible for the acute lymphoblastic leukemia the patients were suffering from.

According to officials at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, where the research was carried out, patients in the trial – some of whom were told in 2013 they had barely a few months to live – not only survived, but now, after the therapy, “have no sign of the disease.”

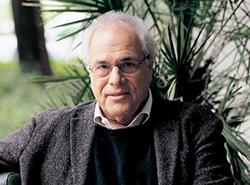

Prof. Zelig Eshhar

The therapy involves extracting T-cells – the white blood cells that fight foreign or abnormal cells, including cancerous ones. Under normal circumstances, T-cells try to fight cancerous cells – but because the body has been weakened by the cancer, the response is usually not strong enough to prevent the spread of cancer. In addition, cancer cells are genetically programmed to evade T-cells, said immunotherapy researcher and oncologist Dr. Stanley Riddell, one of the leaders of the study.

Riddell, along with colleagues Dr. David Maloney and Dr. Cameron Turtle, extracted T-cells from the patients and genetically modified them to develop longer-lasting and more aggressive responses to the disease. As a result, the patients experienced significant improvement – and even elimination of the disease altogether.

“I felt a great sense of satisfaction upon hearing the news,” said Eshhar, an immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science and at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. “The next task of my lab and others working on this is to expand it and try to attack other forms of cancer.”

Eshhar has been conducting T-cell research for over a decade, and in 2014 was recognized by leading industry publication Human Gene Therapy for his work, along with Dr. Carl June of the University of Pennsylvania for their work in the field. In an article called “From the Mouse Cage to Human Therapy: A Personal Perspective of the Emergence of T-bodies/Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells,” published for the occasion, Eshhar laid out the mechanics of CAR T-cell immunotherapy – showing how his work on mice progressed to the point where the American team was able to pick up the cudgel and conduct a study on humans.

With that. Eshhar cautioned Wednesday, the breakthrough did not in any way represent a “cure for cancer” – at least not yet.

“Obviously much more work is needed,” he said. “One issue with this kind of therapy is that you have to develop specific T-cells for each kind of cancer. But studies like those are a great impetus to move forward with research. I believe the day will come when we will see many more cancers treated in this manner.”