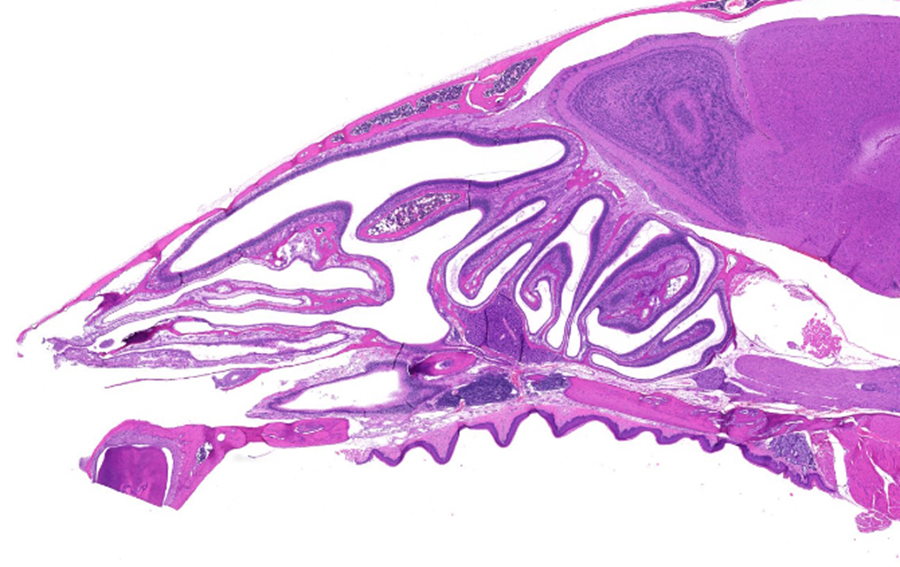

The nose is a major gateway to our bodies – for the air we breathe, the aromas we smell and the microbes that make us sick. On its way in, the air passes through nasal conchae – the long, narrow, curled shelves of bone that look like a shell and protrude into the breathing passage. The conchae are covered by a unique kind of tissue that secretes mucus and contains many branches of nerve cells that are responsible for our sense of smell. The structure and function of the conchae allows the air to warm up and absorb moisture before reaching the lungs.

Not only do the nasal conchae serve as a leading site for pathogen invasion into the airways, but they also have a major weak spot: Because they are located so close to the brain, they are not accessible to the antibodies dispatched by our immune system via the blood stream during an upper airway infection. How, then, are we relatively protected from invading microbes and not constantly sick?

In a new study published today in Nature, researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science discovered that antibody-secreting cells migrate to the nasal conchae whenever we are sick or given a vaccination, and from there they secrete antibodies locally into the nasal cavity. This discovery could pave the way for more effective nasal vaccinations and new treatments for nervous system disorders, allergies, and autoimmune diseases.